This fifth session of BBA 101 explores the intersection of racial status and concentrated poverty. African-American children have historically grown up in separate communities that are much more disadvantaged than those of their white peers, a reality that persists today and increasingly applies, as well, to Hispanic children, especially those in immigrant families. These materials assess how the toxic interactions between concentrated poverty and race put these students at further disadvantage, beyond that of individual or family poverty, and some of the main drivers that we must address if we are to reverse this trend and close associated opportunity gaps.

Required reading

- William Julius Wilson (1987), The Truly Disadvantaged. Chapter 2, Social Change and Dislocations in the Inner City. This seminal book, which documents the impacts of millions of African Americans living in ghettos of concentrated poverty and racial isolation, brought this critical issue to the public’s attention. It also sparked a new body of scholarly research on inter-generational poverty and the mechanisms that sustain a stubborn American underclass. In the chapter “Social Change and Dislocations in the Inner City,” Wilson examines the complex factors associated with racial discrimination. In addition to direct discrimination, urban minorities are affected by changes in the economy and by population shifts, including global migrants. Indeed, Wilson also discusses the impacts of migration on poverty, hypothesizing that the migration of middle-class and working-class families is one factor driving concentrated poverty.

- Patrick Sharkey (2013). Stuck in Place. Chapters 4 and 5. This book, by a former student of William Julius Wilson, continues that line of research to explore how ghetto families have fared and changed over forty years. Sharkey finds that many remain stuck in the same violent, isolated, resource-weak contexts. And in Chapters 4 (Neighborhoods and the Transmission of Racial Inequality) and 5 (The Cross-Generational Legacy of Urban Disadvantage), he illustrates how those circumstances severely limit their life prospects, including substantially reducing children’s academic achievement, above and beyond the impacts of individual student and family poverty.

- Schott Foundation for Public Education (2015). Black Lives Matter: The Schott 50 State Report on Public Education and Black Males Multiple interacting systematic problems drive longstanding achievement gaps, including the gap in high school graduation rates between black and white males. Only nine states reported graduation rates of 70% and above for black male students, while 19 states have a graduation rate of 59% or lower. Data also reveal higher suspension rates and fewer advanced placement opportunities for black males, and thus less opportunity for these students. Data from The Educational Testing Service’s symposium, in the recommended reading of this session, enable the exploration of key factors that reduce black male graduation rates, including poor levels of parental education, high rates of foster care, hunger, and suspension/expulsion, and more.

- Amy Stuart Wells (2014). Seeing Past the “Colorblind” Myth of Education Policy. National Education Policy Center. This article explains how purportedly colorblind policies have led to outcomes that are anything but: from systemic under funding of schools serving students of color to weak and inexperienced teachers in those same schools, lack of access to high-level courses, harsh disciplinary policies, and more. We need to acknowledge and explore how minority racial status affects minority students and work intentionally to counter those forces. This same argument applies to many test-based education policies that have been in vogue for the past decade.

Recommended reading

- Gary Orfield (2013). Closing the Opportunity Gap: Housing Segregation Produces Unequal Schools. Orfield asserts that lack of progress on school desegregation is linked to social inequalities in housing. The lack of affordable housing for low-income families near the best schools further limits opportunity for minority families in particular, as per Rothstein. Data show that the United States will soon have a nonwhite majority, and that its public schools already do, which makes a focus on equal housing and educational opportunities increasingly urgent.

- Jeremy E. Fiela (2013). Decomposing School Resegregation: Social Closure, Racial Imbalance, and Racial Isolation. American Sociological Review. Fiela attempts to explain desegregation efforts in schools through the lens of social closure – the exclusion by some societal groups of others in order to gain a perceived advantage – by exploring the links between segregation, population change, and school racial composition. He asserts that the declining presence of whites in minority schools feeds into the racial imbalance, further isolating minority students, and that the biggest barrier to desegregation today is the uneven racial distribution of students across school districts.

- A Strong Start: Positioning Young Black Boys for Educational Success: A Statistical Profile. Educational Testing Service’s Addressing Achievement Gaps Symposium. These data provide a snapshot of the disparities that young black males face in their lifetime. The report compares data on teacher quality, reading achievement, high school dropout rate, educational attainment, school segregation, grade retention and employment for black male versus white male students. These disparities help explain the graduation rate gap discussed in the Schott Foundation report.

- Richard Rothstein (2013). “Misteaching History on Racial Segregation.” School Administrator. Rothstein gives an overview of the legal history that led to housing, and thus school segregation, including court rulings and regulated housing, and its impact on achievement gaps. He argues that the best way to bridge the achievement gap is through an intensive renewed national focus on integration.

Graphics

EPI Web Articles: Unfinished March. Richard Rothstein and others. In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. called for legal rights, including jobs and a living wage. This infographic shows the inequalities that poor black children still experience today in schools, over 50 years later, limiting their chances of climbing out of poverty and into circumstances of greater opportunity.

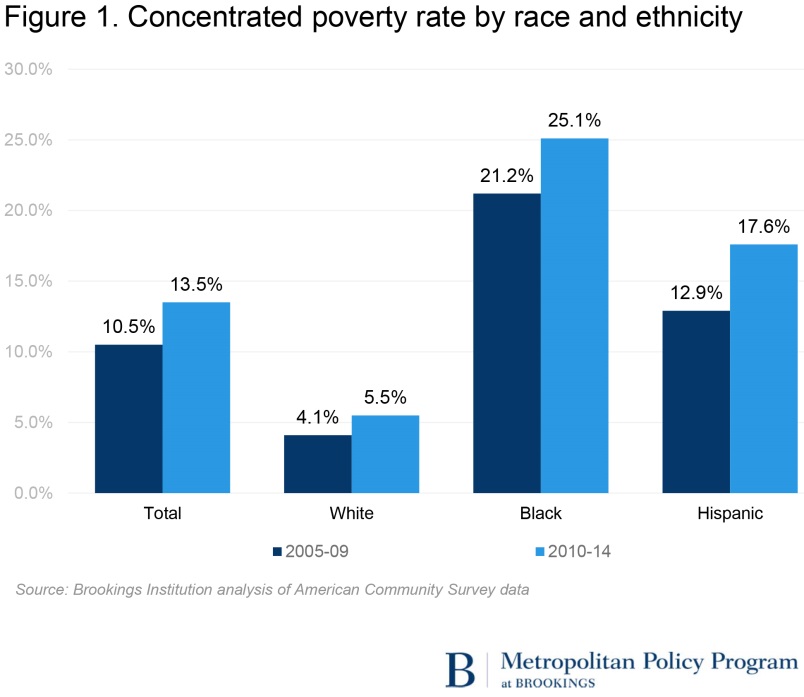

Elizabeth Kneebone (2016). Concentrated Poverty in the wake of the Great Recession. Brookings Institute. Poverty has become both more widespread and concentrated since the recession. Neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, in which 40% or more of the population is living below the federal poverty line, have especially increased since 2009. While concentrated poverty has overall increased for every racial group since 2009, it has always been especially prominent among black communities.

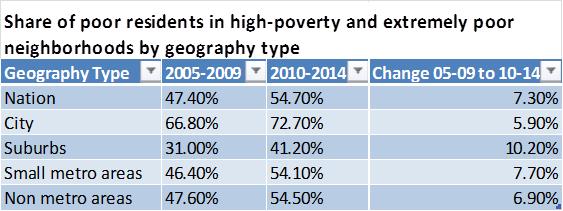

While this report finds that the suburbs have the smallest percentage of residents in high poverty and extremely poor neighborhoods, the percent change from 2005-2009 to 2010-2014 is almost double the change in cities over that period.

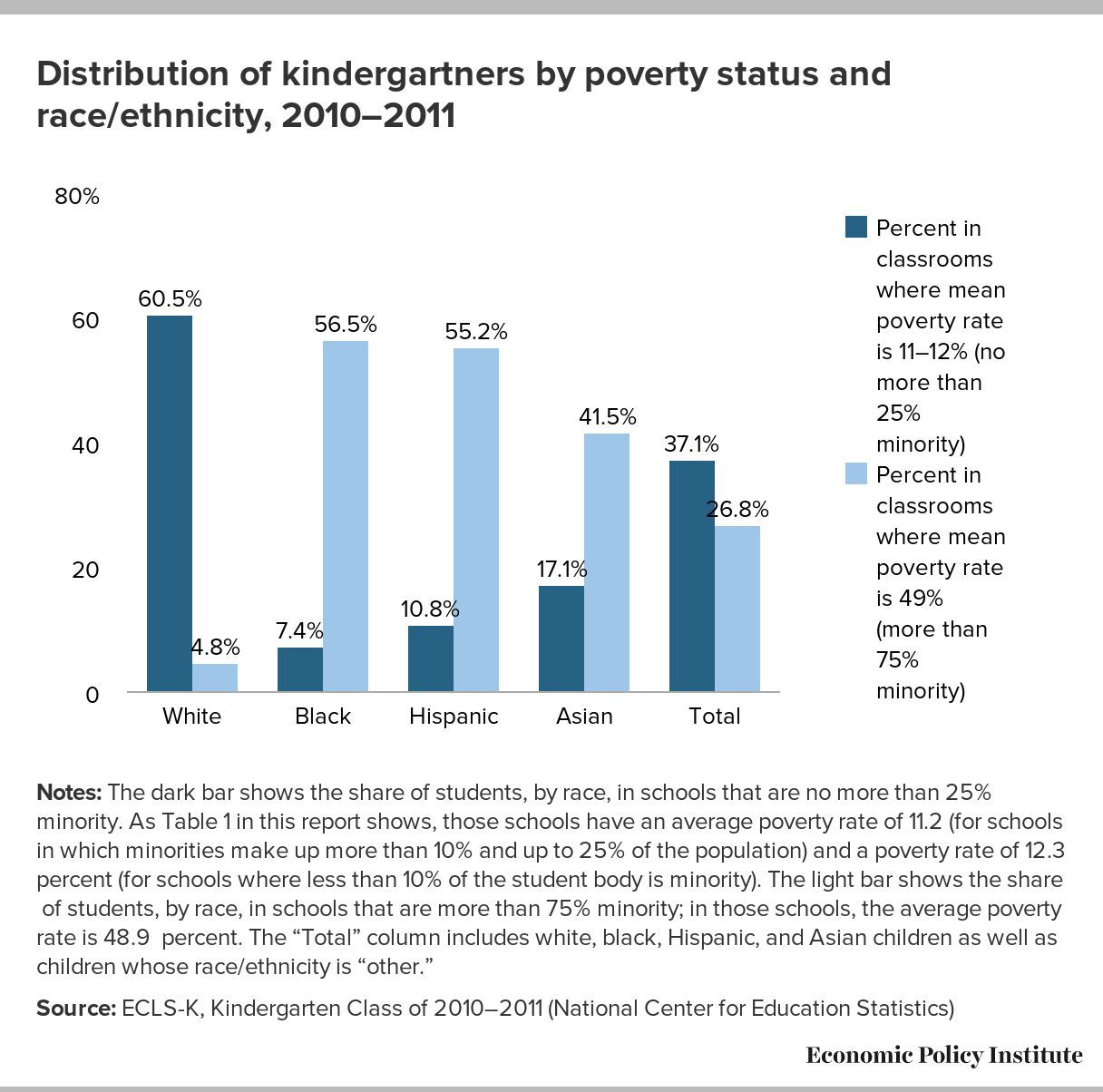

Emma Garcia and Elaine Weiss (2014). Segregation and peer’s characteristics in the 2010-2011 kindergarten class. As the notes indicate, this bar chart illustrates the degree to which students of color – both black and Hispanic – begin school with peers who are low-income, while white students overwhelmingly attend low-poverty schools. Race- and income-based gaps that children bring to kindergarten are thus exacerbated, rather than compensated for, by their school contexts.

Film

The award-winning 2013 documentary The New Public chronicles the daily experiences of a group of high school teachers and their students in their first and fourth years in an alternative small high school in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Director Jyllian Gunther’s powerful film illustrates in stark relief the uphill battles facing teens living in poverty, many in situations of racial and economic isolation and with single parents, as they try to make it to graduation. The students and their parents, teachers, and school leaders highlight the influence of so-called “non-cognitive” skills on the academic outcomes sought, and on particular challenges to school improvement at the high school level.

Study questions

- According to Wilson, Sharkey, Rothstein, Wells and others, race and concentrated poverty have long been associated with each other and posed barriers to student (and family) success. What do you think it will take to end the cycle of concentrated poverty? Is integration in schools and/or housing feasible, and if so, which strategies are most likely to be effective?

- This session discusses various factors – political, social, legal, and economic – that have contributed to problems we face today related to concentrated poverty and its racial aspects. While several solutions have been proposed, some, such as school integration, would take many years to put in place. What can individual schools or school districts do to reduce concentrated poverty, and its impacts, today? Which other partners will be most critical to this work?

- Wells and Orfield are among many to document that minority students are disadvantaged because of the schools they attend. Proposed fixes include various strategies to integrate low-income students into higher-income schools. There is also substantial evidence that such strategies can benefit low-income and minority students. At the same time, do you also see potential downsides to such efforts? For example, might it lead to exclusion or hostility among children? (i.e. students’ different values and backgrounds preventing socializing, bullying, etc.) How can we counter these forces?