Context/Need

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, the elementary school serving students in the Tangelo Park neighborhood of Orlando suffered many of the problems plaguing its counterparts in other low-income urban neighborhoods: it had poor attendance and declining test scores, and nearly half of students from Tangelo Park were dropping out of Dr. Phillips High School.1 Though Tangelo Park is situated just 5 miles from the International Drive tourist area and Universal Studios, the lives of Tangelo Park’s children and their families, 90 percent of whom are African American or Afro-Caribbean, could not have been more different from those of the millions of annual visitors to Disney World and Orlando’s other famous resorts. Originally built to house workers at the former Martin Marietta headquarters (now Lockheed Martin), the Tangelo Park neighborhood suffered from racial and socioeconomic isolation similar to that of many low-income black neighborhoods. Residents had few public services to draw on and limited public transportation options. 2

When Robert Allen was hired as principal of Tangelo Park Elementary School in 1991, he took over a school with a D–F classification that wanted badly to improve its image and connect with the community. Many parents were working multiple jobs and not coming to parent-teacher conferences; some were afraid of the physical walk to school because of rampant crime; and others saw their children’s education as the school’s responsibility. Mobility was also very high. Though most Tangelo Park residents owned their homes, many of the homeowners were grandparents, with children moving in and out frequently, so teachers were often teaching a totally different group of students at the year’s end from those they had met in September.

Response

At the same time, the neighborhood had a palpable sense of pride and was trying to “take back” its streets from crime, drugs, and gangs.3 Longtime resident Sam Butler describes how the community’s unique culture led it to respond forcefully and successfully to the violence it was experiencing:

We were a community of people who had been places, did things—served in the military, worked for corporations like Lockheed Martin—and knew something about what we would like for our community. We had a nucleus of people who were not willing to accept the crime, the drugs, the “mischief” that some other neighborhoods sort of laid down for. We wanted a better place for our children, a safer environment to raise our children. About 10 men got together and said “Hey, we can do something about this.” 4

At the same time that Tangelo Park residents were organizing to improve their neighborhood, Harris Rosen, an Orlando hotelier, was assessing the barriers to school and life success for many of the children across the city. Convinced that the fixes lay in the education system, he reached out to two friends who knew that system well. An initial meeting took place in Harris’ office with Sara Sprinkle, coordinator of early childhood education for the Orange County Public School System and with Bill Spoon, then-principal of Dr. Phillips High School. They decided to design a scholarship program that would provide free tuition, room, board, books, and travel expenses for any Dr. Phillips High School student from a designed neighborhood who was accepted to a state university, a community college, or a trade or vocational school. During the meeting, however, Sprinkle suggested that if the program was to be successful in getting heavily disadvantaged students to and through college, it had to include a preschool component to prepare them for kindergarten. Both Harris and Spoon agreed, and the Tangelo Park Two-Three-Four-Year-Old program was conceived, along with the “Promise” scholarships.

The next step was to identify the right community that needed a helping hand and would be receptive to and likely to benefit from Rosen’s proposed sponsorship. The planning group contacted County Commissioner Mable Butler who “knew of the perfect community and could take you right over there.” She gave Rosen a tour of Tangelo Park, and he agreed that it would be a good fit. The team then met with Tangelo Park Elementary School Principal Robert Allen, who by his own admission was a bit skeptical of Rosen’s plan. Allen suggested holding a community town hall meeting so that the neighborhood’s residents could hear from Rosen himself about the planned scholarship program. As Allen describes it, “A somewhat hesitant citizenry listened to Harris and wondered if the community had to wait 15 years for the promised scholarships, because it would take that long for the early childhood students to graduate from high school. Rosen’s response was ‘We all begin our college scholarship program this June with a working partnership between the Tangelo Park community, the Harris Rosen Foundation, and Orange County Public Schools.'”5

Rosen, the president and CEO of Rosen Hotels and Resorts, had grown up on the Lower East Side of Manhattan as a child of Jewish immigrant parents who had come to the country with virtually nothing. He thus understood both the barriers that Tangelo Park children faced to success in school and the potential of the right interventions to help them overcome those barriers.6 In 1994 he committed funding from his foundation to ensure those supports, which have since expanded substantially. With Rosen’s financial backing, the Tangelo Park Program meets a range of community educational, social, and economic needs through quality child care programs, parent training and supports, and student access to post-secondary education and training opportunities.7

After all of these years working with the Tangelo Park community, we are absolutely convinced that there is as much intellectual talent in our underserved neighborhoods as there is in any of our more affluent gated communities. If that is true, then as the United Negro College Fund suggests, we are sadly wasting millions of minds in our nation, which we simply cannot afford to do.

– Harris Rosen, president and CEO, Rosen Hotels and Resorts and founder, Tangelo Park Program8

Strategy for change

The Tangelo Park Program (TPP) is a community-based initiative that promotes civic commitment by private, public, and community organizations to children’s educational success.9 The initiative has a three-part strategy that is bolstered by access to vocational programs and support from alumni:

- Ensuring that all the community’s children are ready for kindergarten through a combination of quality child care and enriching prekindergarten.

- Supporting parents to be full partners in their children’s education from birth all the way through high school.

- Guaranteeing college scholarships; this guarantee provides not only the hope that Rosen says is key to making college a high priority, but also the practical means to make that hope a reality.10

Coalition

The Tangelo Park Program is governed by a two-tier board: a legal board of officers, and the Community Advisory Board, a functional panel of people who are directly involved with providing services to the Tangelo Park community. The Community Advisory Board has organized the community’s various agencies into one body with a unified agenda, and it works with three sets of partners (including community agencies), to design and deliver comprehensive educational opportunities to each of the neighborhood’s children.11 The three sets of partners are:

- School: Members from schools serving the neighborhood—including Tangelo Park Elementary School’s current principal, its former principal Robert Allen (who now serves as the chair of both the TPP legal board and the Community Advisory Board), a high school counselor, and an early childhood education specialist—are among the leaders of TPP’s programs.12

- Community: Community partners include the Tangelo Park Civic Association (TPCA), which played a crucial role in uniting the Tangelo Park community in the early 1990s to fight off drugs and blight. The TPCA provides information about community events, initiatives, and concerns, and serves as a proactive facilitator and liaison for the community. Tangelo Baptist Church helps families access educational and social services, and the Tangelo Park YMCA provides a variety of out-of-school supports.13 The Tangelo Park Neighborhood Center for Families—a county-sponsored service hub that is located within the elementary school—offers family counseling, pediatric health care, a food pantry, computer and internet access, and more.14 (Unlike the school, TPCA, church, and YMCA, the Center for Families is a state-sponsored agency. So it does not coordinate its calendar with the other TPP community agencies and is not a core partner in the same sense.)

- Outside of the community: The Research Initiative for Teaching Effectiveness, which is part of the Center for Distributed Learning at the University of Central Florida, leads research on and documentation of Tangelo Park’s achievements. In addition, individual volunteers and organizations, such as Junior Achievement, do not sit on the advisory board but provide their services pro bono. Since 2008, Cornell University students have supported many aspects of TPP through Cornell’s Alternative Spring Break program.15

This program is drastically different from others because it wraps both arms around the community and says we are here to serve you and help you become the best person you can be. A lot of these programs, they have only one piece here and one piece there.

– Bernice King, director of the King Center in Atlanta16

Comprehensive services

Through its various programs, TPP provides support, free of cost, to all residents of the Tangelo Park community age 2 to 22 and their parents.17 Services include:

Early childhood education—Ensuring that every child is ready to start kindergarten begins with high-quality day care provided through a network of home-based centers throughout the community. The Tangelo Park child care program (the “2-3-4-Year-Old Program”) began in 1995 with two providers. As of 2017, there were 9–10 providers each year, depending on the number of children, with a caregiver:child ratio of 1:6. Several specifics of the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program are essential to fully preparing children for their K–12 years. All caregivers are 4-C certified in the State of Florida. This certification, a key quality metric, means that providers have at least 45 hours of training coursework, including courses in child care rules and regulations; health, safety, and nutrition; identifying and reporting child abuse and neglect; child growth and development; and behavioral observation and screening. Providers also work under the supervision of a certified early childhood education specialist, who visits each home-based center four times per week to manage the center’s curriculum and program.18

Early childhood education—Ensuring that every child is ready to start kindergarten begins with high-quality day care provided through a network of home-based centers throughout the community. The Tangelo Park child care program (the “2-3-4-Year-Old Program”) began in 1995 with two providers. As of 2017, there were 9–10 providers each year, depending on the number of children, with a caregiver:child ratio of 1:6. Several specifics of the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program are essential to fully preparing children for their K–12 years. All caregivers are 4-C certified in the State of Florida. This certification, a key quality metric, means that providers have at least 45 hours of training coursework, including courses in child care rules and regulations; health, safety, and nutrition; identifying and reporting child abuse and neglect; child growth and development; and behavioral observation and screening. Providers also work under the supervision of a certified early childhood education specialist, who visits each home-based center four times per week to manage the center’s curriculum and program.18

The 2-3-4-Year-Old Program, which is designed to nurture children’s developmental, social, and emotional skills, operates all day, from 7:30 am to 5:00 pm, five days a week and 50 weeks per year—allowing parents to work normal hours. Rosen equips each child care center with computers and printers, which providers use as learning tools. (The Starfall website, for example, offers learning games with shapes, colors, numbers, and letters, helping children learn that foundational material while also gaining familiarity with the computer and mouse.19) Care providers are also supported by a nurse, who works closely with parents and families to “complement home care and day care developmental, educational and psychological milestones.”20

The ECE specialist places children in the homes for child care. She provides learning materials for each care provider on a weekly basis. She makes sure that the homes are in compliance with DCF rules and regulations. She also takes learning activities out to each home during the week and works with the children. Once she’s back on the school campus she has different duties, including teaching a group of kindergarten children each afternoon.

– Patti Jo Church-Houle, Rosen Preschool Director21

Parents of children in the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program also take parenting classes; the parents of two-year-olds are required to take at least two classes during the year. Children who will be entering kindergarten (or younger children who will first be attending Tangelo Park’s pre-K program) are assessed three times during the year for a range of academic skills, information that the program lead uses to help parents work with their children to ensure they are fully prepared for school. The program lead also communicates regularly with pre-K and kindergarten teachers to identify and reduce gaps in student readiness, assure a smooth transition into school, and keep track of students’ progress.22

This has been so good for the children of Tangelo Park. . . . You see a huge difference between kids who did the [2-3-4-Year-Old] Program and those who come from elsewhere.

– Diondra Newton, former principal, Tangelo Park Elementary School23

Tangelo Park Elementary School also has both a pre-K and a Head Start program. In addition to early childhood and parent supports, the Head Start program offers a food pantry and assistance for public utilities and referrals.24

- Family support—In the Tangelo Park Program’s early years, the Family Service Center provided support for day care providers, parents, and pre-K teachers and coordinated activities among different organizations, such as the elementary school, YMCA, and church. More recently, an early childhood specialist from the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program has served as the liaison between the school and community and held parenting workshops at the Family Service Center (which no longer exists) throughout the year. The 2-3-4-Year-Old Program supervisor also conducts hearing and vision checks.25

In addition, a Parent Leadership Training program helps parents address their children’s needs through education on decision-making and positive communication skills. The program, which was initiated by the University of Central Florida, begins by helping parents understand the school system—a common challenge in high-poverty and isolated communities—and goes on to explain the importance of and help them build leadership skills that advance their engagement in and advocacy for their children and their children’s schools.26

- Health care —Vision and hearing screenings are conducted at the elementary school; for other health care needs, parents can take their children to the Neighborhood Center for Families, which coordinates a community health program with a nurse from Health Central—Orlando’s not-for-profit comprehensive community hospital—to provide free physical exams and prescriptions.27

- Enrichment and extracurricular programs —The YMCA provides educational, recreational, and civic activities, from enrichment programs to instructional support for suspended students—with help from Rosen to, for example, hire a lifeguard for children’s swimming classes. The Tangelo Park Baptist Church has established an instructional center, staffed entirely by volunteers—some of whom are former teachers—to help students with homework and help them prepare for important exams, like the SAT.

Starting in March 2008, Cornell University students have come to Tangelo Park each year for an “Alternative Spring Break” week to work with preschool and elementary school students on a variety of projects. The Cornell students help plan and execute science and literacy fairs sponsored by the elementary school. They coordinate with the elementary school principal prior to their arrival in Orlando to help organize the events and plan projects for the elementary students; then they work in the classroom with the teachers during the four full school days they are in Orlando. They also serve as short-term mentors for 6th, 7th, and 8th grade middle school students.28 The mentoring is usually, but not always, limited to the spring break period, and focuses on issues relevant to succeeding in college, including the benefits of attending a local versus an out-of-state college, obtaining/securing financial aid, choosing a major, scheduling classes/homework/study groups, and diversity. University of Central Florida researcher Marcella Bush notes that the Cornell students “challenge Tangelo Park students to get outside of their comfort zone.”29 They also get to attend a board meeting and a reflection session as part of their spring break experience.

Robert Allen also points to teacher coaching that has enabled existing teachers to enhance their skills and build on their passions, with the program evolving over time to enable him to train teachers who in turn coach others. TPP also provides counseling for students starting in elementary and through middle and high school to ensure that they have the academic and other support they need.

- Post-secondary support—The Rosen Foundation Scholarship endowment guarantees all graduating high school seniors who live in Tangelo Park a full scholarship that covers tuition, room, board, and living expenses to any vocational school, community college, or public university in the state of Florida. (These kinds of initiatives are commonly called “Promise” programs. There are now dozens of Promise communities across the country, with Kalamazoo, Michigan—where the Promise program is funded by an anonymous group of local philanthropists—perhaps the best-known example.) Scholarship alumni now provide mentoring to current scholarship recipients (see the “Indicators of progress” section for more information).

When needed, TPP also provides extra support for students who are struggling in college. “We have had a few kids that weren’t taking full advantage of the scholarship program, so we look at their grades, call them in to meet with them one-on-one, and try to figure out what the problem is and provide counseling, maybe looking at a different major if necessary.”30

- Data collection and evaluation—Charles Dziuban, director of the University of Central Florida’s Research Initiative for Teaching Effectiveness (RITE), working with Marcella Bush—part of the Tangelo Park Program’s interagency team — conducts the research on and documents the program’s initiatives and achievements. This includes updating needs assessments in collaboration with the four Community Advisory Board organizations and analyzing the program’s impact. The University of Central Florida also helps facilitate activities for Tangelo Park parents, provides academic tutoring for both students and adults, and offers health screening services, including prenatal care, free of cost within the community.31

Twenty-one years later, with an infusion of $11 million of Mr. Rosen’s money so far, Tangelo Park is a striking success story. Nearly all of its seniors graduate from high school, and most go on to college on full scholarships Mr. Rosen has financed. . . . “We are sitting on gold here now,” said Jeroline G. Adkinson, president of the Tangelo Park Civic Association and a longtime resident of the mostly black community. “It has helped change the community.” 32

Foundational policies and practices

Comprehensive approaches to education like that instituted in Tangelo Park tend to be bolstered both by practices that are specific to a community and by local- and state-level policies that support the program’s mission. At the same time, counterproductive policies can impede an initiative’s mission and make replication of such strategies more difficult. Both types of policies are visible with respect to Tangelo Park. Productive policies and practices are explored in this section, and counterproductive state-level policies are discussed in the following section.

An engaged community helped get TPP started and keeps it strong

One aspect of Tangelo Park that is unusual among areas of concentrated poverty and that has helped it is its high level of homeownership. Because residents in similar neighborhoods tend to rent, they have higher rates of mobility and less social capital. Tangelo Park is also a very small community—just 3,000 residents—making it more cohesive and easier for one philanthropist to support effectively.33

Evidence of the community’s activism and cohesion can be seen in pre–Tangelo Park Program efforts to eradicate drug dealing and combat signs of blight. Robert Allen notes that the community “was ripe” for an early education program and for Rosen’s investments as a whole when the program was initiated in 1993.34

The community’s cohesion is enhanced by the Tangelo Park Program’s grounding in community engagement—the neighborhood’s residents, community organizations, and educators are central to managing it. Child care centers that are situated in neighborhood homes and run by the homeowners, means that each has its own distinct personality. One home specializes in serving many children with developmental disabilities; the owner’s own daughter died at age 42 of complications from Down syndrome, so she has personal experience with issues that children with disabilities face.35

The preschools foster relationships in the community. There are no more than six kids in each home preschool. The schools are operated by a homeowner, who we vet, train, and certify. . . . In essence, they are very much like the neighborhood moms of the 1950s who watched over all the neighborhood kids.

– Harris Rosen36

The Parent Leadership Training (PLT) program grew out of the University of Central Florida’s membership on the TPP interagency team; meetings with the elementary school principal and the YMCA director, along with input from the larger team, led to the development, implementation, and, ultimately, evaluation of the PLT.37 This program also fills a critical gap: an emerging line of research suggests that public schools are designed for middle-class parents who are set up to make key decisions for their children, and that schools thus fail to provide the guidance that less-educated parents rely on.38

College scholarships provide incentives for success in school

As in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and other “Promise” communities, college scholarships have galvanized the Tangelo Park community to ensure that its children are able to take advantage of those opportunities. For example, the Neighborhood Center for Families, which “encompasses non-profit organizations, government agencies, churches, and civic groups, . . . supports families to help them attain the Rosen scholarship.”39 Noradeen Farlekas, who researched several Promise communities as part of her dissertation work, finds that such comprehensive supports are critical: “It’s all about poverty. So in Detroit [another Promise community, but one that lacks this community aspect], of the 25 percent that do graduate from high school, almost none are prepared for even community college—it’s hard for kids to be successful in college if they are only reading at the fourth- or sixth-grade level—and very few can take advantage of the scholarships.”40

Another challenge in Detroit is that its scholarships offer substantially fewer benefits. Tangelo Park Program scholarships are similar to those of Kalamazoo, and both are among the most generous in the nation. They are so-called first-dollar scholarships—meaning that students do not have to first apply for loans and fail to receive them in order to take advantage of the Promise scholarships—and the scholarships cover full tuition plus other core expenses.41 Farlekas points to extensive research showing the barriers to academic and life success—for low-income students in particular—that accruing student debt poses. Structuring scholarships in intentional, generous ways that minimize “red tape” is essential to enabling college completion and averting financial stress down the line.42

State law supports parent engagement, child care programs

- Parent engagement—Federal education legislation—most prominently the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and Title I of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA)—encourages parent engagement in education. In practice, however, it is state and federal requirements and rules that drive the degree to which parents are engaged and their engagement is valued. State legislation enacted in Florida around 2000, which transfers power from central office administration to school advisory councils (SACs), also requires that parents constitute the majority of SAC membership and that the school’s population diversity is proportionately represented.43 These rules laid the foundation for the Parent Leadership Training that has been a powerful resource in Tangelo Park.

- Family day care insurance—In 1998, Florida passed a family day care insurance law, which protects homes that are used for child care.44 Prior to the law’s passage, insurance companies could cancel property insurance for family day care homes, posing a substantial barrier to operating the type of residential day care upon which Tangelo Park families and the program depend.45

Policy challenges

As a small, quasi-independent community supported by a wealthy sponsor, Tangelo Park has been largely cushioned from the impacts of several state laws that might impede the development of similar initiatives in larger communities and that have proven counterproductive for other disadvantaged students across Florida and the schools serving them.

State funding for public education is very low and inequitable

Because the U.S. education system relies heavily on local property taxes to fund public schools, state funding is critical to boosting revenue in low-income areas and evening the playing field for students who live in them. Florida falls short on both of these measures: the Education Law Center, which analyzes and ranks school funding levels and equity, gives the state very low marks across the board.46 Florida ranks 41st of all 50 states in per-pupil funding, providing just over $7,500 per student, well below the median level and substantially less than half of that in the highest-funding state, New York ($18,165). It also receives an F for “effort”—the Center’s calculation of how much Florida spends on education versus its capacity to do so. Both of these are compounded by flat distribution of those meager funds—Florida provides, on average, 97 percent as much funding for schools with 30 percent poor students as it does to schools that do not serve any poor students, so high-poverty schools are not receiving sufficient funds to meet the greater needs they face. Finally, from 2008 to 2014, Florida fell further in the effort index (tumbling 24 percent) than any other state but Hawaii.

These numbers pose major challenges for high-poverty schools, which struggle to compete with wealthier districts for well-qualified, experienced teachers and to provide even a basic education. And while Tangelo Park is shielded from the brunt of this underfunding by the extensive resources Rosen provides, these policies hurt schools like it across the state. As longtime resident and community organizer Sam Butler says, “This really doesn’t make sense. You just sort of shake your head and say, ‘What are [state legislators] thinking?’”47

Moreover, the state’s failure to provide sufficient funding for public education is not limited to K–12 schools. Florida’s Voluntary Pre-K program, which was enacted as a state constitutional amendment by ballot initiative in 2002 after the state legislature refused to enact it, has consistently been among the nation’s worst-resourced and lowest-quality state programs. State spending per child enrolled has declined from just under $2,800 in 2006 to $2,300 in 2015, making Florida 40th in state spending of the 42 states that fund pre-K programs. According to the National Institute of Early Education Research’s (NIEER’s) annual yearbook, The State of Preschool 2015, Florida’s program meets just three of NIEER’s 10 quality benchmarks and none of the benchmarks related to teacher qualifications.48 Early childhood scholar Steven Barnett, president of NIEER, has been a vocal critic of Florida’s program, warning that “Low investment will not yield high results if quality is absent, regardless of how many children participate.”49

Test-based accountability policies have punitive impacts that harm low-income, minority students, schools, and communities

Florida was an early pioneer of policies that rely on students’ scores on standardized tests to evaluate and grade educators and schools and to tie those evaluations to consequences. Although such strategies have been increasingly discredited, the state has retained them, with resulting problems for schools and communities like Tangelo Park.50

In 1999, Florida adopted a school accountability plan that assigns schools a letter grade from “A” to “F” like a report card, based heavily on its students’ test scores on the annual Florida standardized test (the “FCAT”). A growing body of evidence and feedback from educators and other education experts points to not only the system’s flaws but its potential to do harm to high-poverty schools in particular.51 Sam Butler comments that

The grading system in itself is maybe not a bad idea, just on the surface. But what it does is forces schools and principals to focus on passing those tests, so a lot of the school year is spent on trying to get that child to be able to pass some standardized test. I believe that if they just taught the children well, then the taking of the test would take care of itself. We are so busy wrapped up trying to pass tests that some kids can’t even tell you where they live. 52

The negative effects of the A–F grading system have been compounded by other test-score-based policies. In 2010, Florida won a $700 million grant as one of the first Race to the Top state recipients (with $23.7 million going to Orange County, in which Tangelo Park is located). In fulfillment of its state commitments, Florida has enacted laws intended to improve teacher quality, turn around low-performing schools, and integrate the Common Core state standards. Some of these policies have had perverse effects. For example, the School Success Act evaluates teachers and determines their pay largely on the basis of so-called value-added measurements (VAM), which have been found to inaccurately reflect teacher effectiveness, as well as channeling classroom time toward test preparation and reducing teacher morale and, thus, ironically, effectiveness.53

Other state education policies, too, suggest the legislature’s lack of attention to the evidence base supporting a given policy. Florida enacted a tax credit scholarship program in 2001 that uses public education dollars to provide vouchers to private and parochial schools and that was expanded in 2010, in the face of mounting evidence that such vouchers do not benefit the low-income students they purport to help.54 And Florida’s laws authorizing, governing, and regulating charter schools are among the nation’s laxest, contributing to poor outcomes for students; the largest and most-cited study on the academic impacts of charter schools finds that Florida students in regular public schools have greater academic growth than their equivalent peers in charter schools, making the state one of a handful of low performers both in 2009 and in the follow-up 2013 study.55

In all, Florida has a pattern of underinvesting in its public schools—and especially in its most vulnerable students—that poses additional challenges for communities like Tangelo Park and that make the support of donors like Harris Rosen all the more critical.

Funding

The Tangelo Park Program is entirely privately funded, though it benefits substantially from a range of in-kind donations and volunteer efforts.

Annual funding ranges from $500,000 to $1,000,000 for the approximately 500 students who are in preschools, high school feeder patterns, and colleges, community colleges, or other post-secondary institutions in a given year. The New York Times reported in 2015 that Harris Rosen had donated $11 million so far.56 (Researcher Charles Dziuban places the number closer to $13 million.57)

Rosen’s generosity, and the publicity it has attracted, has resulted in other gifts, like that of former Miami Heat point guard Dwyane Wade, who visited Tangelo Park Elementary School during the NBA All-Star Weekend in February 2012 to host what he termed a “Work Hard, Play Hard” rally (part of a larger FCAT rally) and announce a donation to the school of two new basketball courts.58

The Orlando Magic and the Edyth Bush Charitable Foundation have both donated to TPP, and the program has also received several awards from Disney that included monetary prizes.

A National Science Foundation (NSF) grant entitled “Bringing Engineering to Tangelo Park” enhanced the Tangelo Park–University of Central Florida (UCF) partnership through a new project that increased the community’s understanding of high-tech career opportunities to ensure that their students have the skills and knowledge needed to succeed in post-secondary quantitative education programs. The initial meeting brought together a broad range of community and UCF leaders and members, along with Rosen, a representative of the Orange County Public School System, and practicing engineers. And in 2004, TPP held a science day at the YMCA that was a result of activities prompted by the grant (though it was not financially supported by it).

Indicators of progress

The Tangelo Park Program began to deliver benefits for students and their families and schools quickly and has seen those benefits increase over the past two-plus decades. Researchers Charles Dziuban and Marcella Bush, who collect and analyze data on TPP at the University of Central Florida’s RITE, have documented progress on several fronts.59

Academic benefits begin early and are sustained through a comprehensive strategy

- As a result of comprehensive, quality early childhood education, students enter elementary school with well-developed motor, cognitive, and social skills, as well as reading, writing, and basic mathematics skills. The share of children from the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program who are on or above track in elementary school has been at least 70 percent and as high as 82 percent every academic year since 2001–02.60

- And data from the Voluntary Pre-K Assessment, which are aligned with state learning standards, show that nearly two-thirds of children who graduate from the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program already have strong print knowledge skills going into their pre-K year (they meet or exceed expectations). By the end of the pre-K year, all children meet or exceed expectations in print knowledge; virtually all—97 percent—meet or exceed expectations in phonological awareness; and nearly nine in 10 meet or exceed expectations in oral language/vocabulary.61

- In 2008, Tangelo Park Elementary School ranked fourth in learning gains in all of Central Florida, and in 2009, it received the Florida State Literacy Leader of the Year award. It is one of a handful of low-income schools to receive an “A” rating in 2004, 2006, and 2008.62

- Since TPP’s inception, mobility has fallen from about 50 percent to virtually zero.

There is a lot more consistency now, which helps tremendously, as teachers no longer have to work with a different class of kids from the start of the year to the end. Teacher morale has really picked up now that they have time to work with kids, the kids come into pre-K and kindergarten programs already able to read, and parents are so engaged. We even have dads coming in to volunteer and getting engaged. The difference [the Tangelo Park Program has made] is like night and day.

– Robert Allen, former principal, Tangelo Park Elementary School, and chair, Tangelo Park Community Advisory Board63

- Between 2005 and 2012, at least 90 percent of Tangelo Park’s high school students earned a regular four-year diploma, with a 100 percent graduation rate in 2011 and 2012. In comparison, the state’s rate climbed from 59 percent in 2004 to 76 percent in 2013.64

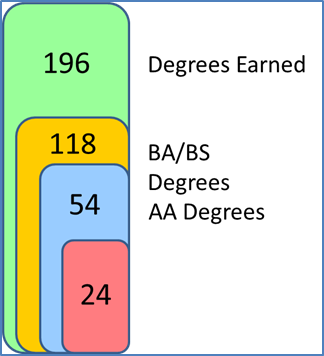

- Nearly one-third of Tangelo Park graduates who enter community college and who remain in Tangelo Park complete an associate degree, while those who choose a vocational school complete at a rate of 83 percent. Of high school graduates who enroll in four-year post-secondary schools, 78 percent attain a degree, and of those who go on to graduate school, almost all (over 90 percent) complete those programs.65

These rates far exceed state and national averages for low-income and minority students. An estimate based on income would have predicted 50 college graduates since 1994 (or 9–12 percent of students); in that time, 118 TPP students have earned bachelor’s degrees and 54 have completed associate degrees (including 32 who earned both). And of the 118 bachelor’s degree earners, 24 have finished graduate degrees, including three doctorates.66

These rates far exceed state and national averages for low-income and minority students. An estimate based on income would have predicted 50 college graduates since 1994 (or 9–12 percent of students); in that time, 118 TPP students have earned bachelor’s degrees and 54 have completed associate degrees (including 32 who earned both). And of the 118 bachelor’s degree earners, 24 have finished graduate degrees, including three doctorates.66

Harris Rosen recalls the difference from 1993—when he asked how many children wanted to go to college, and just two or three hands went up—versus a year later, after the scholarship was announced—when “every hand went up.”67 And the share of students who are eligible for scholarships but leave Tangelo Park before graduating and thus cannot take advantage of the scholarships has fallen sharply, from over half in 1994 and 1996 and about one in four in the early 2000s to virtually none in 2012 and 2013 (2 percent and 1 percent, respectively).68

It caused me to really focus. I took honors classes, became highly involved in extracurriculars [at Dr. Phillips High School] . . . It was a really big deal for me.

– Shanathan Crayton, 1999 high school graduate, who got a bachelor’s degree at Florida A&M University, completed two master’s degrees, and is now a grant coordinator for Miami Dade College

[Mr. Rosen] has taken the burden off me and my entire family. He opened up a lot of doors.

– Ariana Plaza, 2015 graduate of Dr. Phillips High School who entered the University of Central Florida as a pre-med student

When people have the resources to go and succeed, there’s a ripple effect. It becomes generational. No one in my family ever went to college before, but now, my baby sister can’t even picture a life without college. My mother even went back and got her degree. I showed her that she could do it.

– Donna Wilcox, who used her Rosen scholarship to earn a bachelor’s degree at the University of Central Florida and then went on to get a master’s degree at the University of Georgia

- One study estimated the early economic benefits of TPP by comparing changes in high school completion and college attendance rates in Tangelo Park with rates among Florida students of similar backgrounds over the same time period.69 University of Western Ontario professor Lance Lochner found that high school graduation rates increased by about 17 percent and college attendance rates by over 30 percent after the introduction of the program, with an estimated resulting increase in lifetime earnings of roughly $50,000 per student. Based on these impacts, along with smaller benefits from reduced crime, Lochner estimates the total annual benefit to a cohort of Tangelo Park students to be $1.05 million. This means a societal return of seven to one from Rosen’s investments, since his nearly $13 million investment would lead to a societal gain of just under $90 million, or about seven times what he had spent (at that time).

- As of 2015, Rosen had distributed nearly 450 college scholarships, including 20 among the 2015 graduating class of 25 students.70 Because each successive cohort of graduates is better able to secure its own scholarships, the share of his support going to college scholarships has declined—currently the spending on the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program is twice the spending on college scholarships—and overall the amount of support needed from Rosen has gone down.

- Moreover, because of the generous scholarship program, Tangelo Park graduates are finishing college without student loan burdens. While the share of U.S. bachelor’s degree recipients with student loan debt has risen from 59 percent to 77 percent over the past two decades, and the average amount of student loan debt has risen from $12,850 to $31,850 over that period, TPP graduates have no student loan debt at all.71

The community as a whole has seen its quality of life improve

A neighborhood once plagued with crime and in disrepair is now thriving. Crime rates fell sharply in the program’s initial years, as did mobility rates among both residents and students, and the average home in Tangelo Park, which was worth $45,000 in 1993, is now valued at $150,000. Dr. Dziuban views the drop in student mobility from over 50 percent to virtually zero as a clear reflection of the incentives to stay that are provided by the scholarships and other program opportunities.72

Economist Lance Lochner estimates the monetary benefits of the reduction in crime in Tangelo Park—in particular a reduction in assaults, which are very costly for residents—from the year of the program’s inception to a decade later.73 Relative to other, comparable communities in Florida and to the state as a whole, he found much larger reductions in crime in all of the categories he measured but robberies. Lochner estimates savings for the community of between $270,000 and $300,000.74

While it’s not clear exactly how much of this positive change is due to the Tangelo Park Program and how much is attributable to broader trends (such as a national drop in crime), both residents and law enforcement officials see TPP as a major driver. Orange County Sheriff Jerry L. Dennings says that “the quality of life [in Tangelo Park] has improved significantly” and, as a result, his officers no longer have to make frequent stops there.75 And Lt. Lynn Stickley of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office says, “We now consider Tangelo Park to be an oasis.”76

Former scholarship beneficiaries have often come back to the community to offer support. In 2013, that support became more structured when a group of Rosen Foundation Scholarship graduates formed the Alumni Association, which now includes a mentoring program to support current scholarship recipients.

The community also benefits indirectly from the strong parental involvement in children’s education that is driven by the structure of the Tangelo Park Program. The early childhood programs have been intentionally designed to foster a strong sense of neighborhood culture and collaboration. And the Parent Leadership Training (PLT) piloted in Tangelo Park has led the parents who have participated in it to take a more active role in their children’s school activities, from helping their children with homework to communicating more with teachers, volunteering in classrooms, and even becoming members of the school government. Two researchers who assessed the impacts of PLT report that “During the graduation ceremony [for the first ‘class’ of PLT participants], school administrators and the YMCA staff described the changes they noted in parents. The elementary school principal, for example, reported that all the new [School Advisory Council] officers were former PLT participants.”77 Research shows that such parent involvement and leadership, which is rare in places like Tangelo Park, is key to enabling advocacy on behalf of the school that drives improvements from better funding and infrastructure to effective instruction. And because stronger schools make for stronger communities, the entire neighborhood benefits.

Tangelo Park’s success drives outreach to other communities

The Tangelo Park Program has been featured in the University of Central Florida’s magazine Pegasus and several other local Florida publications; in the New York Times; and on MSFE-TV Channel 24’s local series “Family Works” (where it was the subject of the series’ first broadcast, in 1995).78 It has also received several Walt Disney World Community Service Awards, including the 1995 Bob Allan Award.79 The TPP Parent Leadership Training has been recognized in well-known education journals such as Urban Education.

Together with representatives from the University of Central Florida, Tangelo Park residents gave presentations promoting TPP at Sloan-C International Conferences on Asynchronous Learning Networks in Jacksonville, Florida, in 2000 and 2003, and also in Washington, D.C.80 Board members also presented at teacher education conferences in 1999 in Washington, D.C., and in 2000 in Jacksonville. Parent Leadership Training representatives have provided parent leadership trainings in Orlando’s Parramore neighborhood (see the next section for more about Parramore) and elsewhere. In fact, program leaders and residents found themselves speaking so frequently with visitors interested in replicating the program that they developed a document offering guidance on how other communities could get organized to do so.81

In April 2017, the work of Dziuban and Bush and their RITE team to support, evaluate, and disseminate information about the accomplishments of the Tangelo Park Program was recognized through the University of Central Florida’s inaugural Collective Excellence award. Provost Dale Whittaker, who presented the award, along with a $15,000 stipend to expand the team’s work, said “the new award will recognize a team each year whose work exemplifies one of seven categories: powering partnerships, creating access, dreaming big, unleashing potential, harnessing scale, amplifying impact or transforming lives.”82

The program is being expanded to Orlando’s Parramore neighborhood

With Tangelo Park solidly successful, in the fall of 2015 Rosen began to plan for the extension of the program in the downtown Orlando neighborhood of Parramore. (As mentioned in the previous section, Parent Leadership Training representatives from Tangelo Park laid some of the groundwork for the expansion through trainings of Parramore parent leaders in 2001 and 2002.83) In addition to providing scholarships for graduates of Jones High School in Parramore, the program will provide preschool for two- and three-year-olds at a new pre-K–8 school for neighborhood students; the school will be built and managed by the district but the preschool wing will be furnished and staffed with funding from Rosen as per his negotiations with the district.84 In addition to the main building, the school—which will serve 800–900 students from preschool to grade 8—will include on its 14-acre campus a Boys & Girls Club, a health clinic, and athletic fields. Physical health care services will range from well-child and sick visits, vaccinations, and pediatric medication to X-rays and specialty referrals. Students will also receive preventive and emergency dental care, along with counseling and case and medication management to address their mental health and wellness needs.85

This expansion represents a substantially greater challenge than the one Rosen took on more than 20 years ago: Parramore is five times the size of Tangelo Park; it is home to a large public housing project; and it has a more transient population.86 Rosen had expressed hopes that the ambitious move would help persuade others like him to make similar investments; one such investment has already been committed. Before the new school has even opened, the University of Central Florida’s College of Medicine promised to provide full scholarships to any student who attends the new pre-K–8 school, graduates from Jones High School, and attains an undergraduate degree at the University of Central Florida.87

This expansion represents a substantially greater challenge than the one Rosen took on more than 20 years ago: Parramore is five times the size of Tangelo Park; it is home to a large public housing project; and it has a more transient population.86 Rosen had expressed hopes that the ambitious move would help persuade others like him to make similar investments; one such investment has already been committed. Before the new school has even opened, the University of Central Florida’s College of Medicine promised to provide full scholarships to any student who attends the new pre-K–8 school, graduates from Jones High School, and attains an undergraduate degree at the University of Central Florida.87

In May 2016, Rosen presented college scholarships to the first 15 Jones High School graduates since the inception of the Parramore Program. One of the recipients, Jahquetta Jones, who had a 3.9 high school GPA, plans to study criminal justice at University of Central Florida and would like to work for the Orlando Police Department and, eventually, the FBI.88 She is currently enrolled at Valencia College, a local community college, where she finished her first semester with a 3.66 GPA. Among the second group of Jones High School graduates under the Parramore Program (the Class of 2017), of the 32 eligible for scholarships, three are the 2nd-, 10th-, and 12th-ranked students in the class. The slated salutatorian has already been accepted to 14 colleges, most of which are offering her full scholarships, including her first choice, the University of Florida, where she would like to study medicine so she can become a neurosurgeon.89

Rosen looks forward to more Tangelo Park and Parramore students seeing clear paths to bright futures and taking advantage of the supports he has put in place to pave the way. As longtime resident Sam Butler notes, the impact on the Tangelo Park community has been nothing short of transformative:

[Rosen’s commitment to providing scholarships and the comprehensive supports he provides to make them viable] has been the shining light in this program. It has given our children in this community an opportunity to dream dreams and then see those dreams come to fruition. 90

Contact: Robert Allen, chair, Tangelo Park Program, Inc., 407-484-4245 or [email protected], or visit www.tangeloparkprogram.com

Acknowledgments

The author extends thanks to Drs. Charles Dziuban and Marcella Bush of the University of Central Florida for their assistance with background information and data on the Tangelo Park Program, and to Noradeen Farlekas for sharing insights from her research on Promise communities. The author also thanks Tangelo Park residents and community leaders—including Robert Allen, Sam Butler, and Patti Jo Church-Houle—for their gracious help and contributions to this case study. Finally, deep appreciation goes to Mr. Harris Rosen for generous time spent responding to questions about the program and, most importantly, for making it happen.

Endnotes

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015. Dr. Phillips High School is the feeder school for Tangelo Park.

- “Big Enough,” Pegasus: The Magazine of the University of Central Florida, Summer 2012.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Robert Allen, April 19, 2017.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Sam Butler, May 4, 2017.

- “Tangelo Park Program” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- “Big Enough,” Pegasus: The Magazine of the University of Central Florida, Summer 2012.

- “Tangelo Park Program” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- Quote provided to Elaine Weiss in conversation with Mary Deatrick, assistant to Harris Rosen, May 2017.

- The initiative was called the Tangelo Park Project in its initial three years, but has been the Tangelo Park Program since 1997, according to Patti Jo Church-Houle. In 1998 the Rosen Foundation created an endowment for Tangelo Park Program, Inc., which was established as an official 501(c)(3) organization and now had sustained support.

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Sam Butler, May 4, 2017.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Robert Allen, April 19, 2017.

- “Tangelo Park Program” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- “Tangelo Park Neighborhood Center for Families” [webpage on the Community Coordinated Care for Children, Inc. (4C)website].

- Tangelo Park Program [website].

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Parents with infants get information from Tangelo Park’s 2-3-4-Year-Old Program about child care facilities in the area. TPP had explored having neighborhood child care centers care for infants as well but the costs and regulations posed obstacles, so they recommend that parents look for 4-C certified providers but do not subsidize costs. (Information provided by Patti Jo Church-Houle in emails exchanged with Elaine Weiss in May 2017.)

- Information provided via email by Patti Jo Church-Houle, Rosen Preschool Director, May 1, 2017.

- The Starfall website is a free, publicly available service provided by the Starfall Family Foundation.

- The nurse is funded by Harris Rosen. See the “2-3-4-Year-Old Program” webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website.

- Elaine Weiss email conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, May 2017.

- Email conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, May 2017. See the “Indicators of progress” section for results of assessments.

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- “Tangelo Park Program” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- Elaine Weiss email conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, May 2017.

- Sheila Y. Smalley and Maria E. Reyes-Blanes, “Reaching Out to African American Parents in an Urban Community: A Community-University Partnership,” Urban Education vol. 36, no. 4 (2001), 518–533.

- Conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, who had conducted screenings years ago, and who also reports that the school nurse subsequently did them.

- “Cornell University: Cornell Alternative Spring Break” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- Elaine Weiss email exchange with Marcella Bush, June 12, 2017.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Robert Allen, April 19, 2017.

- Sheila Y. Smalley and Maria E. Reyes-Blanes, “Reaching Out to African American Parents in an Urban Community: A Community-University Partnership,” Urban Education vol. 36, no. 4 (2001), 518–533.

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015. Note that per researcher Charles Dziuban, the $11 million figure cited in the New York Times article is lower than the actual investment, which was nearly $13 million by 2015 (Elaine Weiss email exchange with Charles Dziuban, June 2017).

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Elaine Weiss conversation with Robert Allen, April 19, 2017.

- Lauren Roth, “Tangelo Park Program Reshapes Generations in Neighborhood,” Orlando Sentinel, November 8, 2014.

- Jim Gibbons, “The Tangelo Park Model for Transforming a Troubled Neighborhood: A Q&A with Florida Hotelier and Philanthropist Harris Rosen,” The Philanthropy Roundtable.

- Sheila Y. Smalley and Maria E. Reyes-Blanes, “Reaching Out to African American Parents in an Urban Community: A Community-University Partnership,” Urban Education vol. 36, no. 4 (2001), 518–533.

- Annette Lareau, Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

- “Family Programs: Neighborhood Center for Families” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- Elaine Weiss phone conversation with Noradeen Farlekas, April 4, 2017.

- This system contrasts, for example, with Say Yes to Education, whose district-wide Promise scholarships in Syracuse and Buffalo, while including dozens of private institutions as well as public colleges and universities, are last- versus first-dollar and thus likely provide a weaker incentive for students to do the work needed to take advantage of them.

- Noradeen Falekas, “A New Application of Social Finance: Combining Impact Investing with Philanthropy to Increase Positive Educational Outcomes and Reduce Incarceration in Low-Income, High-Crime Neighborhoods” (DLP diss. Northeastern University, 2016).

- Sheila Y. Smalley and Maria E. Reyes-Blanes, “Reaching Out to African American Parents in an Urban Community: A Community-University Partnership,” Urban Education vol. 36, no. 4 (2001), 518–533.

- Leaders of the Tangelo Park Program describe playing an important role in the law’s passage. See Florida Statute 627.70161.

- Elaine Weiss email conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, May 2017.

- Bruce Baker, Danielle Farrie, Monete Johnson, Theresa Luhm, and David G. Sciarra, Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card, 6th ed. (Rutgers, New Jersey: Rutgers Graduate School of Education and Education Law Center, 2017).

- Elaine Weiss interview with Sam Butler, May 4, 2017.

- W. Steven Barnett, Allison H. Friedman-Krauss, Rebecca E. Gomez, Michelle Horowitz, G.G. Weisenfeld, Kirsty Clarke Brown, and James H. Squires, “Florida,” in The State of Preschool 2015: State Preschool Yearbook (National Institute for Early Education Research, 2016).

- Jeff Solochek, “Florida’s Big, Bad Prekindergarten Program,” Tampa Bay Times, April 10, 2012.

- See, for example, Baker et al., Problems with the Use of Student Test Scores to Evaluate Teachers, Economic Policy Institute Briefing Paper no. 278, August 29, 2010; Edward Haertel, Reliability and Validity of Inferences about Teachers Based on Student Test Scores, William H. Angoff Memorial Lecture, Educational Testing Service, March 22, 2013; and Getting Teacher Evaluation Right: A Brief for Policymakers, American Education Research Association and National Academy of Education, 2013.

- For example, the Board of Directors of the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) issued a statement expressing opposition to the policy, which has since been adopted by numerous other states and school districts. See “A–F School Rating Systems” [webpage on the NASSP website].

- Elaine Weiss interview with Sam Butler, May 4, 2017.

- Edward H. Haertel, Reliability and Validity of Inferences about Teachers Based on Student Test Scores, Educational Testing Service, William H. Angoff Memorial Lecture, 2013; Tim Walker, “NEA Poll: Nearly Half of Teachers Consider Leaving Profession Due to Standardized Testing,” NEA Today, November 2, 2014.

- Martin Carnoy, Vouchers Are Not a Proven Strategy for Improving Student Achievement, Economic Policy Institute, February 28, 2017; Kevin Carey, “Dismal Voucher Results Surprise Researchers as DeVos Era Begins,” New York Times, February 13, 2017.

- Edward Cremata, Devora Davis, Kathleen Dickey, Kristina Lawyer, Yohannes Negassi, Margaret E. Raymond, and James L. Woodworth, National Charter School Study 2013 (Stanford, Calif.: Center for Research on Education Outcomes [CREDO] at Stanford University, 2013).

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Elaine Weiss email exchange with Charles Dziuban, June 2017.

- Christiana Lilly, “Dwyane Wade Hosts Fatherhood Round Table with White House Staff, Visits School during NBA All-Star Weekend,” Huffington Post, February 24, 2012.

- While these data have not been published, they have been presented at several academic conferences. For example, these data were presented by C. Dziuban and P. Moskal in the conference session “20 Years: What the Data Show and What They Don’t,” October 29, 2015, at the EDUCAUSE 2015 Annual Conference, Indianapolis, Indiana.

- Patti Jo Church-Houle has tracked these data from the program’s inception. Three times each year—in the fall, winter, and spring—Church-Houle assesses the children in the 2-3-4-Year-Old Program who will be going into either pre-K or kindergarten the following year., She assesses the children for a range of learning goals, such as shapes, colors, numbers, letter sounds, and the ability to write their own names and birthdays. She also shares the information with parents, so they know how to help their children be better prepared for school, and she checks in with kindergarten teachers to track 2-3-4-Year-Old Program graduates’ progress in their first (pre-K or kindergarten) school year.

- Information and data from Sharetta Taylor using data from the Florida Department of Education re VPK assessment, beginning and end of the year.

- Documented in the TPP 15th anniversary report; recorded in Community Advisory Board meeting minutes as reported by the school principal.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Robert Allen, April 19, 2017.

- Data from Tangelo Park provided by Charles Dziuban. Data on Florida’s high school graduation rates from Florida Department of Education Information & Accountability Services, Florida’s High School Cohort 2015–16 Graduation Rate.

- Charles Dziuban, Presentation on Tangelo Accomplishments (Tangelo Park Program website).

- Charles Dziuban, Presentation on Tangelo Accomplishments (Tangelo Park Program website).

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Charles Dziuban, Presentation on Tangelo Accomplishments (Tangelo Park Program website).

- Lance Lochner, “Measuring the Impacts of the Tangelo Park Project on Local Residents: Preliminary Report,” June 2007.

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- Mark Huelsman, The Debt Divide: The Racial and Class Bias behind the “New Normal” of Student Borrowing, Demos, May 2015.

- Charles Dziuban, Presentation on Tangelo Accomplishments (Tangelo Park Program website).

- Lance Lochner, “Measuring the Impacts of the Tangelo Park Project on Local Residents: Preliminary Report,” June 2007. Lochner used data from the Orange County Sheriff’s Office on the number of motor vehicle thefts, burglaries, and robberies, as well as assaults and larceny. Note that comparison communities were “other communities of different sizes and which experienced different amounts of population growth.”

- Lance Lochner, “Measuring the Impacts of the Tangelo Park Project on Local Residents: Preliminary Report,” June 2007.

- Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015.

- From transcription of unpublished interviews with Charles Dziuban and Marcella Bush, verified by Marcella Bush, May 2017.

- Sheila Y. Smalley and Maria E. Reyes-Blanes, “Reaching Out to African American Parents in an Urban Community: A Community-University Partnership,” Urban Education vol. 36, no. 4 (2001), 531.

- “Big Enough,” Pegasus: The Magazine of the University of Central Florida, Summer 2012; Lizette Alvarez, “One Man’s Millions Turn a Community in Florida Around,” New York Times, May 25, 2015. (The MSFE-TV television series is not available online.)

- Sandra Mathers, “Tangelo Park Wins Disney Top Prize,” Orlando Sentinel, June 21, 1995.

- “Tangelo Park Program” [webpage on the Tangelo Park Program website].

- “Replicating the Tangelo Park Program” provides a nine-step template and provides answers to four key questions: (1) What steps does a community need to do to build [a] Community Action Board? (2) What empowers community members to address the needs of the community? (3) What increases the community’s awareness of community needs and local resources? and (4) How do you keep members interested in serving on the board?

- “New Award Recognizes Collective Excellence at Founders’ Day,” University of Central Florida Colleges & Campus News (accessed June 1, 2017).

- Tangelo Park Program 15th Anniversary Report, “Timeline of Events.”

- Annie Martin, “Orange Schools Spell Out Details of Rosen Pact at Parramore School,” Orlando Sentinel, October 13, 2015.

- Elaine Weiss notes from conversation with Patti Jo Church-Houle, March 22, 2017.

- Dave Chase, “8 Steps That Could Save Employers $500 Billion and Boost Education,” Forbes, June 22, 2015.

- Caitlin Dineen, “Officials Unveil Plans for New $41.3M School in Parramore Neighborhood,” Orlando Sentinel, January 24, 2015.

- Annie Martin, “Harris Rosen Presents College Scholarships to 15 Jones Graduates,” Orlando Sentinel, May 17, 2016.

- Selina Wells-Harris, Rosen Parramore PS-8 Scholarship Eligible Student Report, January 26, 2017. TPP internal document provided to Elaine Weiss in May 2017.

- Elaine Weiss interview with Sam Butler, May 4, 2017.