Context/Need

In 2008, when CJ Huff was recruited to lead Joplin, Missouri’s schools, his main charge was to raise the district’s high school graduation rate, then at 73 percent. Having served as superintendent of the high-poverty school district of Eldon, Missouri since 2004, Huff recognized that high and rising student poverty rates, and the disconnect between the Joplin community and its schools, posed challenges to achieving that goal. He also knew that to enable Joplin’s teachers to do their jobs effectively, he would have to alleviate the daily stresses and trauma their students experienced due to hunger, violence, and homelessness.

Response

Huff convened a team of parents, educators, and community members to conduct one-on-one conversations with faith leaders, business leaders, and social services officials with a stake in improving their city’s schools. Over nine months, those conversations helped the team identify the core components of a plan—eventually called Bright Futures—to engage the community, tackle poverty-related impediments to learning, and, ultimately, transform the education system. They believed they could substantially raise the graduation rate and create a college-going culture that would permeate the schools from the ground up.

Peggy Fuller, vice president of Southwest Missouri Bank and an early member of the team, describes a key moment in the initiative’s evolution:

In April 2010, before we even had a name, we had a “community breakfast” where we wanted to introduce the idea to community leaders and give them a sense of the real need that existed in our town to step up and partner with our schools. We asked for help at the end of that breakfast, hoping that three or four people would agree to take on leadership positions, and we ended up with 50 who wanted to help! That’s when we knew we had struck a chord. But now we had a different problem: we had 50 people who wanted to get involved and needed to put them to work quickly. So we formed “ambassador teams” and went out in groups of three or four to visit every single school building in Joplin over the course of three weeks. We asked the same questions at every school [including]: “What do you need from your community?” “What are your biggest challenges?” and “How can more volunteers help you?” From that data-gathering project, we identified six “now needs” that we could begin working on immediately. It is my opinion that the ambassador teams were crucial to the early success, because it showed the school personnel immediately that we were serious about changing things and investing.

In 2011, a new challenge arose: Joplin was hit with one of the worst tornadoes in U.S. history, killing 161 people, including seven students, and causing nearly $3 billion in damage.1 With the Bright Futures framework in place, however, Huff and his team were able to turn that tragedy into opportunities for the district’s schools and particularly for some of their most disadvantaged students.

Strategy for change

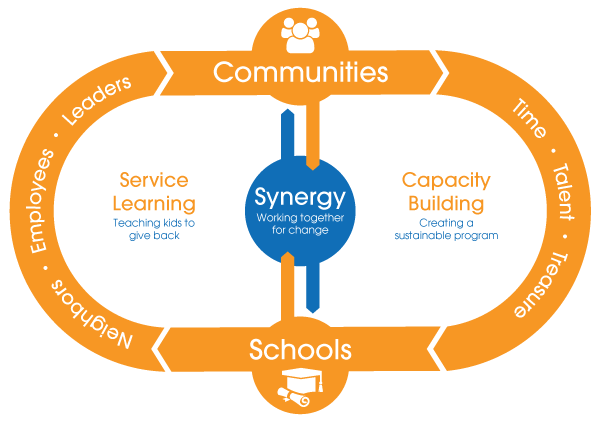

Huff and his staff knew that schools alone could not address all of the needs that teachers and counselors were identifying. They also knew that district superintendents (and mayors and principals) come and go, so engaging parents and a broad range of community leaders would be necessary both to their immediate efforts to support students and to ensure that their efforts would be sustainable long term. So they worked to get the entire community to take ownership of its schools, and to view the schools as key to Joplin’s success.

Their plan had three main components:

- Ensuring that every child’s basic needs could be met within 24 hours, using a three-tiered system of support that included tapping into local human service agencies, churches, social media, and local fundraising.

- Cultivating and building community leadership capacity to meet longer-term needs and establish the partnerships required to solve some of the greater problems faced by the youth in the community.

- Encouraging service as a part of the school culture, so that children, teachers, and schools gave back to the community, and so that all students, particularly those accustomed to receiving help, would understand their power to give and grow into the engaged citizens that Joplin (and all communities) need.

Coalition

Bright Futures began in Joplin and has since become a national organization called Bright Futures USA, with affiliate communities in seven states. This case study discusses the evolution of the program in Joplin, now called Bright Futures Joplin. Though CJ Huff is no longer superintendent his work was instrumental and quotes from him about the initiative’s beginnings help explain its success.

Bright Futures Joplin has developed relationships with roughly 100 local institutions, including the school district, social service agencies, and dozens of business and faith institutions. Through these diverse partnerships Bright Futures delivers a broad range of services and supports to the district’s students and their families.

- The Joplin School District has taken the lead in providing enhanced mental health services, before- and after-school opportunities, mentoring, and internships, and in supporting career-and-college readiness.

- Social Service Agencies working with Bright Futures include the City of Joplin and Joplin Health Department, as well as the Economic Security Corporation and Western Missouri Legal Services. Private agencies include the Boys and Girls Club of SW Missouri and Joplin Family YMCA as well as the United Way of SW Missouri and SE Kansas. As service providers, they are equipped to support a broad range of student needs and interests that complement the services Bright Futures leverages from the school district and business and faith communities.

- Business Community Members including dozens of local businesses, from restaurants and car dealerships to banks and utility companies, work with Bright Futures, providing in-kind donations, services, and other supports.

- Faith Institutions that work with Bright Futures include St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, Young Life Christian ministry, Mount Hope Church of Christ, and over a dozen others. Mount Hope member Frank McReynolds, for example, consistently attends Site Council meetings for Royal Heights Elementary School, and worked with students to develop a recycling campaign, pick up recycled materials, and deliver them to a recycling center. He also serves as a lunch pal for a fifth-grade student and helps communicate the school’s needs to his congregation. Various members of the congregation come to the school to help teachers with special classroom projects.

One great example of faith involvement in [Joplin’s] schools is South Middle School and Calvary Baptist Church, which is next door and up a hill from the school. Before Bright Futures, the members of the church would talk about “that school down the hill.” After they became partners and worked together, the members began referring to South as “our school down the hill.” It’s an emotional connection that is very powerful. It’s all about people feeling welcome in the schools.

Steve Patterson, director of missions, Spring River Baptist Association and board member, Bright Futures USA

Comprehensive supports

In order to fulfill its mission of tackling poverty-related impediments to learning and transforming the education system, Bright Futures works with its coalition partners to provide a range of supports for students and their families.

Early Childhood Education.

Like many other communities employing comprehensive strategies to better meet children’s needs and boost their strengths, Bright Futures in Joplin is focused on helping families establish stronger foundations for learning for their children, especially those most likely to enter school already behind. Bright Futures leadership knew that, because many of the district’s most vulnerable kids didn’t go to center-based day care or preschool, they could not necessarily reach them through those mechanisms. They also did not want to duplicate efforts among the many organizations that were already doing great work in this area, such as the Joplin Public Library, Dolly Parton Imagination Library, Parents as Teachers, and United Way Success by Six. So they identified leaders from a few of those groups who could work together to determine ways for Bright Futures to best support those organizations in meeting their respective goals. They focused on educating adults in each child’s life about the importance of reading to them and finding convenient places to connect and engage them.2

- Reading Matters—Some at-risk students arrive at kindergarten never having held a book in their hands. In response to teachers’ concerns about the gaps they saw in literacy and other school readiness skills, Bright Futures has developed the Reading Matters campaign. Public service announcements on area radio stations that emphasize the importance of early reading are complemented by other initiatives designed to get books into the homes of low-income children and their families.3

- The Bright Futures Reading Matters Committee has also recently established another early childhood support program, to expand the health information provided to new parents to include support for early learning. The committee purchased new books, literature on the importance of reading to babies, and a promotional reusable neoprene bib with the reminder to “Read to Me: 30 minutes, Every Child, Every Day” with the goal of delivering them to every new mother in Joplin. The committee currently works with both Joplin hospitals, and works with a number of government entities, including the area Health Department, Joplin Public Library, Joplin Parents as Teachers, and LifeChoices, to consistently communicate to parents the importance of reading daily to young children. The committee hopes to secure future funding to sustain this effort going forward as well as provide similar resources to area day care providers and the parents they serve.4

- Little Blue Bookshelf—In partnership with United Way SW Missouri and SE Kansas, Bright Futures places age-appropriate new and gently used books in locations that are frequented by families that are unlikely to have books at home.5 Based on research showing that a lack of books in the home, and thus access to them, is a major barrier to poor parents’ reading to their children, the project aims to enable all parents to read to their young children at least 30 minutes every day, so that every child has enjoyed the benefit of 1,000 hours of reading by the time he or she enters kindergarten.

- Lend & Learn Library—United Way Success by Six operates a “toy library” in the Joplin United Way office, open five days a week. Parents and their pre-kindergarten aged children can play with age-appropriate toys in the library, and parents can check out toys and books to use at home. Parents also use the space to connect with one another and enable social time for kids.6

- Born Learning Trail—In summer 2015, in partnership with Target, United Way Success by Six, and the regional United Way, Joplin opened its first Born Learning Trail.7 The trail offers a series of outdoor games for young children and their parents and other caretakers to explore together, with opportunities to play, talk, and sing with kids and to learn about nature. Every child who attended the ribbon-cutting ceremony received a new book as a gift.

- Prekindergarten—Some Joplin preschoolers are served through the state’s pre-K program, but it has too few slots to serve all the children who would like to attend. As such, one of the goals of Bright Futures leadership is the construction of a new early-childhood learning center, which would ideally serve all children whose families request the program. Progress has begun on the center: early childhood classrooms were moved from the trailers they had occupied since the 2011 tornado to temporary space in the old Duenweg Elementary School as of fall 2016, and designs for a new 40,000-square-foot building with capacity for over 500 children, which incorporated extensive input from early childhood teachers, were put before the School Board in September.8 Funding for construction, estimated at $10 million, will be split, with $5 million in Community Development Block Grant funding each from the city of Joplin and the state of Missouri.

Academic Enrichment

While Bright Futures was founded with the goal of alleviating poverty-related barriers to learning, its third component, service learning, reflects the initiative’s commitment, as well, to ensuring deep and meaningful learning for all students. Over time, this precept has spurred a range of enrichment activities, both within classrooms and throughout the community, some specifically created by Bright Futures and other inspired by it directly or indirectly.

- Mentoring—Volunteers from the community have helped establish several mentoring programs to ensure that all students have the “safe adults” they need in their lives. Students who are struggling with school can get help through weekly tutoring and mentoring programs: Together Reaching Every Kid (TREK) for elementary students and Bright Futures Friends (BFF) for middle school students.9 And through a separate program, Positive Adults Lunching with Students (PALS), adult volunteers have lunch with at-risk students each week at school. After lunch, PALS volunteers read to, play with, or just talk to their “lunch buddies.”

“We have forged a very positive relationship that begins each week with a hug. My life is better because of the opportunity I have to sit and talk with my Lunch Buddy each week. Our recent conversations have involved everything from why cussing is bad, to understanding the importance of hand washing, and the idea that Santa still comes to your house even if you can’t get a Christmas tree.”

—adult PALS lunch buddy testimonial10

- Service Learning—In keeping with the Bright Futures’ philosophy of communities supporting and taking ownership of their schools, schools are structured to give back to communities as well. Service learning, the third leg of the initiative’s model, ensures that teachers and students enjoy the deeper learning that comes from hands-on classroom experiences. Among younger students, service learning activities might involve cleaning up trash in a local creek bed, while older students engage in more sophisticated, curriculum-enhancing activities such as collecting and analyzing water samples and providing the data to local public agencies. CJ Huff believes that this is an essential part of a 21st century education because “true service learning is an incredible way for kids to learn about what compassionate, involved citizenship is all about.”11

- Operation College Bound—For at-risk children, one obstacle to graduating from high school and transitioning to postsecondary education is a lack of early exposure to those options and to role models to whom they can relate would provide inspiration. Joplin thus adopted Operation College Bound (OCB), a program launched at Columbia Elementary School by a group of teachers who got inspired at a Model Schools Conference. The goal of OCB is to expose kindergarten through fifth-grade students to six different college campuses during their time in elementary school.12 Through these visits students learn about careers that might be of interest to them and how higher education can help them fulfill their goals and aspirations. OCB career day brings representatives from local businesses to school to meet with students to discuss future career paths and how a college education fits those paths.

- Transitions Programs—Research shows that transitions from elementary to middle school and from middle to high school are the most vulnerable points for at-risk students—the times when they are most likely to check out mentally and drop out physically. Bright Futures Joplin has been working to smooth those transitions and better support students through two peer-to-peer programs: Where Everybody Belongs (WEB) for the transition to middle school and Fusion for students who are moving to high school. The goal is to help younger students acclimate and get and stay engaged in their new schools. This program enjoys support from faith-based youth leaders, relevant human service agencies, and several business/corporate sponsors.

Fusion in particular has been enormously successful. We’ve had Fusion students come present to our board and do a better job than many of my banker friends! The experience it gives these students is incredible. They are taught leadership and mentoring skills that will improve their lives forever.—Peggy Fuller

- New Schools Designed to Foster Academic, Behavioral, and Social Development and enhance college, career, and life readiness—The tornado that ripped through Joplin in May 2011, devastating a large share of the city and leveling two schools, also provided new opportunities in its wake. A combination of insurance proceeds, donations, local taxes, grants, and tornado relief funding enabled the district to build five new schools. Schools Superintendent CJ Huff leveraged those funds to improve conditions for some of the district’s most disadvantaged students and to design new schools that would drive 21st century learning goals.

The new Soaring Heights School serves both elementary and middle school students in a combined building that takes advantage of economies of scale, such as a shared kitchen and state-of-the-art auditorium, while keeping younger and older students separate for academic, sports, and other activities. Low-income students from an old and run-down school were redistricted so that they would be among the primary beneficiaries of this beautiful new school filled with natural light and chock-full of smart spaces inspired by teachers’ suggestions, from “fidget chairs” in classrooms to a glassed-in “outdoor classroom” that can be opened to let in fresh air on nice days and used virtually year-round.

The new Joplin High School, which opened its doors in September 2014 after two years of construction, houses five distinct career path academies, which are designed to ensure that students are academically ready for postsecondary learning or jobs and that they have the broader set of abilities needed to succeed in those contexts, including succeeding in skilled work. The centers range from the STEM-focused Franklin Technology Center to a performing arts academy. The latter houses not only classrooms and performance space for drama, band, choir, orchestra, and debate students, but “also includes a 1,250-seat auditorium that will continue to bear the name of former music teacher T. Frank Coulter; a black-box theater with indoor and outdoor seating; music rehearsal halls with sound-isolating practice rooms; and a community safe room that will be open to the public during stormy weather.”13 These investments were among the factors that led the U.S. Department of Education to include Joplin on its fall 2015 list of just nine districts deemed to be “future ready.”14

Wraparound supports

Wraparound supports are at the heart of Bright Futures’ mission of alleviating poverty-related barriers to teaching and learning. These have focused mainly on ensuring that immediate needs are met, as per the first of the initiative’s three core precepts, but also extend to longer-term concerns.

- Addressing Immediate Student Needs—The first of the three Bright Futures components explained earlier is a three-tiered system of supports to meet students’ basic needs within 24 hours—so that students are not distracted by unmet needs but can focus on their studies. Use of existing human service agencies is the cornerstone of the effort, with effective communication among and between agencies essential. Awareness of which agencies are available and what they can provide is key, as is the facilitation of regular meetings among providers. The agencies’ representation on the district Bright Futures Advisory Board and on school-based Bright Futures Councils also helps. In addition, a donation center called Darla’s Room is stocked with clothing, shoes, school supplies, and other donated items for use by teachers, counselors, and other school staff. In order to meet more unusual needs, Bright Futures employs a second tier, the Bright Futures Joplin Facebook page. Through it under-resourced students have secured such items as a pair of size 13 steel-toed work boots needed for a new welding class and a suit and dress shoes for a job interview.

A third tier, the Eagle Angel Fund, provides backup support to the first two, as determined by the Joplin Advisory Board. It is noteworthy that the need to draw on this fund has diminished over time, as the first two tiers have gained strength through better alignment of community resources and communications among agencies. Today, the fund is typically used for “gap funding” to provide immediate financial support to high-need families (for rent, utilities, etc.) while Bright Futures Leadership gets the right agencies involved to provide support.

- Health—Through partnerships, various health care providers in the school district volunteer services to support needy children’s well-being. The services may include conducting a physical exam to enable a student to participate in an after-school activity, dental services for a student with a cavity, or even mental health services for a student coping with trauma or other issues.15

- Nutrition—Through the Snack Pack program, children who need them receive weekend backpacks filled with food and snack items so that they do not go hungry on weekend days when school meals are unavailable. Community volunteers get together each week to stuff over 500 snack packs with items that are donated by churches and local businesses; the cost per pack is about $5. A nutritionist and the district food services department work to ensure that the food is both nutritious and shelf-stable.16

When I first heard about Bright Futures, I was elated to learn our schools were teaming up with faith-based and business partners that would be working together with social services in our community to meet both immediate and long-term student needs. We had never had anyone outside of our parent-teacher organization show concern about our students in this way. Teachers were so used to seeing a need in our classroom and running to a store after school to purchase an item(s) for a student or recognizing a need but not being able to meet it for monetary reasons. When Bright Futures was put in place, teachers simply needed to verbalize a need to our counselor, make a phone call, or send a quick email to have the need met. We were amazed at how quickly needs were met. Clothing needs were met within hours. The support from our community had never been stronger. We (educators) had a tremendous weight lifted off our shoulders. We had dozens upon dozens of people loving our students and filling needs. We had students who were sleeping on their couches or receiving their first bed. Students received backpacks full of school supplies. Schools were asked to make room so Bright Futures could stock our shelves with extra school supplies. We no longer had to worry if our students would be warm enough as they walked to and from school because they were given coats, sweatshirts, and stocking caps. Families were given food baskets for Thanksgiving and Christmas. Parents were given presents to place under the tree for their children.

Brandi Landis, teacher, Kelsey Norman Elementary School

Family and Community Engagement

To cultivate and build community ownership of and leadership for schools, Bright Futures establishes Bright Futures Councils in each school building. The councils, which operate independently under the direction of the principal, include a mix of business, human services, and faith-based partners, as well as parents. They meet with the school periodically (monthly or quarterly, depending on the needs of the school) to discuss how to help school leadership and staff address needs and reach their goals. Members of the councils, who are considered partners, vary across schools. Following are some examples.17

- Cecil Floyd Elementary—Three churches (St. Paul’s United Methodist Church, New Creation Church, and Grace Baptist Church), three businesses (Qdoba, Casey’s General Store, and Snodgrass Collision), Legal Aid of Western Mississippi, and two local nonprofits (Independent Living Center, which serves individuals with disabilities, and Lafayette House, which works to end domestic violence and sexual assault) serve on the council for this school.

- East Middle School—This school’s council members hail from Wildwood Baptist Church, the neighborhood Walgreens, US Bank, Hampshire Pet Products, the Kyle Hickham Agency, and Missouri Southern State University.

- Joplin High School—This school’s council members come from First Presbyterian, First United Methodist, and Fellowship Baptist Churches, as well as Young Life, a youth ministry program; several health care institutions, including Freeman Health Systems, Mercy, Ascent Recovery Residences, and Orthopedic Specialists of the Four States; businesses, including Qdoba, Walgreens, LifeChoices, Allgeier, Martin & Associates, and Able Body Manufacturing; and Missouri Southern State University, which has also been involved in supporting Bright Futures in other capacities.

Bright Futures also leads a Leadership Academy program which provides community members with intensive leadership training, instructing them on how the Joplin School District works, giving them a chance to ask questions of district leaders, and guiding them to explore how their actions can help improve students’ lives and the district. The academy covers such topics as poverty and the impact it has on learning, how the leadership structure of the district works, and the district’s vision for the future.

Practices and Policies

The ability of Bright Futures to improve student and school achievement, and, recently, to scale up and spread to dozens of districts across seven states (as of 2016), is due in large part to specific internal practices as well as district, state, and federal policies that support this work.

Community engagement

As discussed above, meaningful engagement of the entire community—from parents of children in schools to leaders in the social services, business, and faith fields—is central to the Bright Futures strategy. Indeed, the assumption that superintendents and other local leaders will come and go, a reality that poses challenges to school improvement efforts in districts across the country, makes cultivating leadership among a broader set of stakeholders critical to longevity.

One challenge Bright Futures encountered from the start was trying to avoid duplicating existing efforts in its community engagement work. “There are tons of organizations already providing these services,” notes board member Peggy Fuller, clarifying that the initiative’s job is to “let folks know that these exist, and then to fill the gaps where they don’t.” She cites as an example, Crosslines, a “great community organization that provides clothing and household goods to families in need. Before Bright Futures, a counselor who saw a child wearing flip flops in January might say ‘Tell mommy to go to Crosslines and get shoes,’ but a mom working the factory line at Pillsbury can’t get to a place open from 10-2. So Bright Futures gives kid shoes now, and then mom has time to get to Crosslines for other needs in the future.”18

Time, Talent, and Treasure

Bright Futures relies on the “three Ts” that it believes are abundant (in varying proportions) in every community: time, talent, and treasure. Acknowledging that the districts in which it operates are not wealthy ones, and that many are struggling, Bright Futures USA Board member and local pastor Steve Patterson maintains that even the poorest community members, whether individuals, churches, or small businesses, have something to give in the form of one or more of those Ts. One especially vivid example is a school assembly that superintendent Huff attended at Emerson Elementary in Joplin, one of his most impoverished schools, in January 2011. When he walked in, Huff noticed that every student was wearing a knitted stocking cap, all of them different colors, some with stripes and others not, but all clearly handmade. When he asked a parent to explain the story behind the hats, she told him that two older women, members of the poorest of the town’s Baptist churches, had hand knitted the hats for every child in the school. With winter coming, knowing that many families were struggling to put aside even a few dollars for gifts, the Bright Futures Council at Emerson realized that this was a need that must be met.

“These two ladies took it upon themselves to tap into their time, talent, and treasure (yarn) to meet the need of stocking caps for every child. The result was a warm and very colorful group of students who saw how much their community cares for them and are likely to be eager to give back.”19

CJ Huff, former superintendent, Joplin School District

Challenges

While Bright Futures can count many successes in Joplin and in its work with other Missouri affiliate districts, some policies have served as obstacles in certain areas and prevented further scaling up.

Prekindergarten. While Missouri receives relatively high marks from the National Institute for Early Education Research for the quality of its pre-K program—meeting 8 of 10 benchmarks— the state ranks below average on per-pupil spending for pre-K and near the bottom, 39th of 50 states, on access. Pre-K reached only 30 percent of the state’s school districts in 2015 and served just four percent of Missouri 4-year-olds and two percent of 3-year-olds.20 As discussed above, Joplin parents who want to send their children to pre-K have access to a program in only one elementary school, thus the need for Bright Futures leadership to work toward opening a new early childhood center.

School funding. The Education Law Center’s National Report Card places Missouri in the middle of the pack with respect to per-pupil funding in 2012; it ranked 29 of 50 states at $9,529.21 But that level puts it much closer to the lowest-spending states, Utah and Idaho, which invest roughly $6,500 per student, than the highest spenders, Alaska, New Jersey, and New York, which spend roughly double that of Missouri. Moreover, Missouri ranks close to dead last with respect to equity in funding among school districts, earning an “F” as one of the six most regressive states in the country. Rather than using state funding to compensate for inequities due to disparities in local property tax revenues, Missouri has a state funding scheme that compounds those inequities, channeling more funds to already wealthier and lower-needs schools, and depriving schools struggling to serve poor students—like many of those in Joplin—with the resources they need to do so effectively.

Political. Even in politically progressive school districts, it can be difficult to establish systems that compensate for the disadvantages that children living in poverty face. So the ability of Bright Futures to garner widespread support for the notion that “all children are our children” and that the community has a responsibility to ensure their well-being is particularly noteworthy. That support is not universal, however. In March 2016, at a forum for candidates for the Joplin School Board, while four prospective members expressed strong support for the continued work of Bright Futures, three others vocally opposed it. The latter candidates argue that it is not the community’s responsibility, but rather that of families, to address children’s needs, and urged an end to some of the funding that is fundamental to Bright Futures efforts.22 Subsequent battles between Bright Futures and the school board led Bright Futures leadership to establish an independent home for its funding.23

Staffing. Very limited dedicated funding for Bright Futures, due both to the political challenges described above and lack of major philanthropic support, means that staffing is minimal. As of the 2016–2017 school year, a single director manages Bright Futures in Joplin, so some projects that might have been adopted and successfully run with more personnel are not feasible. For example, Bright Futures had previously worked with teachers and schools to produce and sell Chrismas cards that local businesses could customize, with proceeds going to support families unable to afford holiday meals or gifts. But given the project’s time-intensive nature, demands on teachers at the very start of the school year, and relatively small return, the program will cease unless a group of dedicated volunteers adopts it.24

Funding

As a relatively new initiative, Bright Futures USA has not yet secured funding from major national philanthropic foundations or from federal government grants. It thus cannot leverage those sources to support affiliates, but relies on a combination of state and local public and private funds, including corporate support. These sources include all funding since 2010:

- Public (grants, Title I funding directed to Bright Futures efforts, etc.)

- The Corporation for National Community Service (Americorps)25 funded year-long volunteer positions for three years, enabling Bright Futures to place VISTA members in some affiliate communities, to move the initiative along at a more rapid rate locally, and to place some volunteers in the home office to help develop processes, search out best practices, and share them across the network.

- State Department of Education funds were designated to expand the program throughout the state of Missouri.

- State Department of Economic Development funds supported trainings at the Bright Futures annual conference.

- The Economic Security Corporation of Southwest Missouri supported trainings, in particular on poverty education, at the conference.

- Private (foundation, corporate, and/or individual grants)

- AT&T, which has a focus on dropout prevention, along with Daryl and Patricia Deel, the David Parks Revocable Trust, DLR Group, Southwest Missouri Bank, and Walmart all provided funds to support general program expansion.

- American Century Investments Foundation and the Jean Jack & Mildred Lemons Charitable Trust supported programming for reading tutors, mentorship, and Operation College Bound.

- The United Way of Southwest Missouri and Wells Fargo helped fund Rebuild Joplin (an organization born out of Bright Futures after the tornado)

Indicators of Progress

Bright Futures leaders believe that test scores, and even broader metrics of academic progress, are only some of the measures of student well-being against which schools, districts, and states should be assessed. Moreover, while Joplin is among many districts focused on raising graduation rates, other Bright Futures districts target a diverse range of goals, from increasing the number of low-income students taking Advanced Placement courses to reducing student suicides. Bright Futures leadership thus works with each affiliate to identify metrics of relevance to that district, and encourage funders to broaden the scope of indicators of student progress they use to decide what to fund and how to gauge the efficacy of their investments.

Academic Gains

Joplin’s leaders also recognize that basic academic measures, including test scores and graduation rates, are among the benchmarks by which schools and districts are judged, and the district has seen substantial progress on those since Bright Futures began.

- Scores on the ACT, widely considered to be a key measure of “college and career readiness,” increased by 14 percent among students who qualify for free-and-reduced-price lunches, from an average of 17.74 in 2008 to 20.19 in 2012.26 This means that Joplin’s low-income 12th graders improved from the “not good” range to slightly above the national average during the first years of Bright Futures implementation. The increase in the share of low-income seniors taking the ACT was even more impressive: that figure rose by 242 percent over those years.27

- The high school graduation rate increased from 73 percent in 2008 to 87 percent in 2015.28 Joplin’s graduation rate also rose at a much higher rate than that of the state as a whole, from 77 percent to 87 percent between 2012 and 2015 (a 13 percent increase), versus from 84 percent to 88 percent (a 5 percent increase) across Missouri.29

- Over those same years, the cohort dropout rate fell from 6.4 percent to 2.8 percent.30 Joplin’s African-American students made slightly greater progress than Joplin students overall (the rate fell from 6.9 percent to 2.5 percent) and there were smaller but still substantial gains for Hispanic students, for whom the dropout rate fell from 5.2 percent to 3.8 percent.31

Other Gains

The new partnerships and supports Bright Futures has brought to the district are evident both in increased engagement and improved outcomes for students.

- Volunteerism is up substantially as are the services volunteers are able to provide. Between 2008 and 2012, community partnerships increased by 850 percent, from just 34 to 289.32 District-wide volunteerism rose over 700 percent from 2008 to 2012, with nearly 1,000 new volunteers working in schools across the district. One result of this is that 194 more adults are now serving as mentors and tutors than five years ago. As of 2012, Bright Futures was able to serve over 690 food insecure children through its “Snackpack” program.

- Attendance, a proxy for student engagement and important predictor of achievement, likewise increased over this time period for all students, while the racial and ethnic gap in attendance closed.33 Joplin High School attendance rates increased 3.7 percentage points between 2008 and 2012, rising from 91.3 percent to 95 percent overall. Black students, who had lagged their white peers by 1.5 percentage points, saw that gap close, with attendance increasing from 92.5 to 96 percent. Hispanic students, too, closed the gap with their white peers, as their attendance rate rose from 94 to 95.5 percent.

- Reportable discipline incidents dropped by more than a third over the same period, from 3,648 in 2008 to 2,376 in 2012.34

- Service learning is having a powerful impact on kids and the community:

- Franklin Technology Center: Joplin High School students at the Franklin Tech center engage in a variety of high-end service projects that leverage students’ evolving science and tech (and more general handyman/woman) skills. For example, in March 2013, a group of students helped install heating and air conditioning for the Watered Gardens expansion of a women’s shelter and in September they built and installed hand rails on the entrance of the new addition.

- Support for Moore, Oklahoma students: Two years after the tornado devastated much of their town and several of their schools, Joplin students learned of similar devastation in Moore, Oklahoma. In addition to losing their school, students in Plaza Towers Elementary School had lost seven classmates who were killed by the tornado. Soon after that, Joplin fifth-graders independently developed a plan to raise funds and books for a replacement library for the Moore students. The presentation even included the cost of renting a bus, including gas and tolls, to transport the Joplin students so that they could deliver the gifts and talk with the Moore students about their own experiences healing from the tornado. The result was so heartwarming that the Today Show sent a reporter to cover it.

“Although most Bright Futures councils are composed of adults in business, faith-based, and human service communities along with school representatives, the Royal Heights [Elementary School] council is testing out a new concept—students as leaders and decision makers! The service learning/Bright Futures council changed its structure the 2013/2014 school year beginning with a service project and has been going strong ever since. Over the summer they researched community organizations and needs that exist, volunteered at various locations, and even received a State Farm grant to help their cause of helping others. This group also identified the need for curbside recycling in our community. They researched the issue, marketed their ideas, and are now encouraging everyone to get registered, and then get out and vote on Proposition A at the April 8, 2014 election. The Proposition missed passing by a small margin but we couldn’t be more proud of their efforts.”35

Principal Jill White, Royal Heights Elementary School

Community and Policy Reach

Just over five years after Bright Futures began in Joplin, it has expanded substantially in terms of both scope and reach/impact.

- Growth, numbers, and new interest: By the time Bright Futures hosted its third annual conference in March 2016, it was attracting over 800 people from nine states. Participants included representatives from most of its then-40 affiliated districts across seven states—Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Iowa, Virginia, and North Carolina—as well as people from 67 other, non-affiliate districts. The conference also brought together 75 district superintendents, for whom Bright Futures sponsored a separate working lunch. (As of September 2016, Bright Futures leaders were working with eight additional communities that have since expressed an interest in moving toward affiliation.)

- Regional impact: Communities are working together to pool resources to support kids across districts. This regional collaboration was on display at the conference, where Carl Junction, Missouri, won a Bright Futures Affiliate of the Year award for its success in getting needed winter coats to neighboring affiliate Avilla, a community of only 100 or so residents.

- Awards: Bright Futures in Joplin and the Joplin school district have also received numerous local, state, and national awards.

- State: Missouri National Education Association Horace Mann Award

- National: American School Board Journal Magna Award, Together for Tomorrow recognition by the White House, Corporation for National and Community Service, and Future-Ready School District designation by the United States Department of Education. On May 21, 2012, one day before the one-year anniversary of the devastating tornado, President Barack Obama delivered the graduation commencement address to Joplin High School.36

- Business: 37

- In the fall of 2012, Gov. Jay Nixon announced a $1 million grant to the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce Foundation to help establish an Innovation Campus at Joplin High School / Franklin Technology Center. The goal of the Innovation Campus program is to help under-resourced students prepare for success in college and careers. Through the program, the Joplin Area Chamber of Commerce, Missouri Southern State University, and Crowder College partner with JHS/FTC to offer numerous dual credit courses to students and to help qualifying students pay for these courses through grants. Dual credit courses enable students to earn college credit while still in high school, giving them a jump start on college and saving them time and money.

- Joplin HS earned the Apple award through 2017, its second such award.38

Bright Futures has been a blessing in our community, not just to the students we impact every day, but to adults like me whose lives have been dramatically enriched by the privilege of being involved.

—Peggy Fuller, 2015 Bright Futures Community Champion

Contact: Kim Vann, Executive Director, Bright Futures USA, [email protected], or Peggy Fuller, former Co-Chair of the Bright Futures Joplin Advisory Board, [email protected]

Endnotes

1. SF Gate, “Damage from Joplin, MO tornado: $2.8 billion.” May 20, 2012. http://www.sfgate.com/nation/article/Damage-from-Joplin-Mo-tornado-2-8-billion-3571524.php#photo-2958987

2. Elaine Weiss conversation with Peggy Fuller, October 17, 2016.

3. Bright Futures Joplin, Reading Matters. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/reading-matters/

4. Email correspondence with Peggy Fuller, Oct. 14, 2016.

5. United Way, Little Blue Bookshelf Project. http://www.unitedwaymokan.org/little-blue-bookshelf-project

6. United Way Success by 6 Southwest MO and Southeast KS Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/mokansuccessby6/photos/a.1580597875523760.1073741828.1534101920173356/1652010005049213/?type=3&theater

7. United Way Success by 6 Southwest MO and Southeast KS Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/mokansuccessby6/photos/pb.1534101920173356.-2207520000.1448325820./1626367797613434/?type=3&theater

8. “The new building will have a capacity of about 260 students in the morning session and 260 in the afternoon session. In addition to early childhood education programs, it also will offer half-day day care options to families that are already enrolled in the preschool session.” Emily Younker, “Joplin early childhood staff elated to use Duenweg school, even temporarily; Design for new early childhood center completed, ready for board approval.” Joplin Globe. August 22, 2016. http://www.joplinglobe.com/news/local_news/joplin-early-childhood-staff-elated-to-use-duenweg-school-even/article_3b3c2e8c-3f2b-5beb-9928-3c32f177bc36.html

9. Bright Futures Joplin TREK webpage. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/trek/

10. Bright Futures Joplin PALS webpage. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/pals/

11. Conversation with Elaine Weiss, September 2016.

12. Operation College Bound Facebook page. https://www.facebook.com/OperationCollegeBound?fref=ts

13. Younker 2016.

14. “Joplin school district earns future ready, Apple awards,” Joplin Globe. Nov. 26, 2015. http://www.joplinglobe.com/news/local_news/joplin-school-district-earns-future-ready-apple-awards/article_76065bbc-12c4-5d5b-88bb-9a7af43ef101.html

15. District leadership had been hoping to add a school-based health center in one of the schools, but the School Board rejected that proposal.

16. Bright Futures Joplin Snack-Pack webpage. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/snack-pack/

17. Bright Futures Joplin School partners webpage. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/school-partners/

18. Peggy Fuller conversation with Elaine Weiss, October 17, 2016.

19. Conversation with Elaine Weiss, September 2016.

20. National Institute for Early Education Research. Rutgers University. State Pre-K Yearbook, 2015, 108-109. http://nieer.org/sites/nieer/files/Missouri_2015_rev1.pdf

21. Bruce Baker, David Sciarra, and Danielle Farrie. Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card. Spring 2015. Education Law Center. http://www.schoolfundingfairness.org/National_Report_Card_2015.pdf

22. Emily Younker, “School board debates Bright Futures request for salary support,” Joplin Globe. May 10, 2016. http://www.joplinglobe.com/news/local_news/joplin-school-board-debates-bright-futures-request-for-salary-support/article_5f654fa1-9155-50c5-8301-68e5907fd1f2.html

23. Because the Bright Futures budget was housed within the school district budget under an “activities” line item (in order to avoid having to file as an independent 501(c)(3) and undergo associated logistical and financial barriers), the board was able to prevent it from spending as needed, including on staff, forcing cut-backs. BF leadership responded by reaching out to the Community Foundation for the Ozarks to ask it to act as Bright Futures’ fiscal agent. They have since engaged in fundraising specifically for Bright Futures to ensure that spending can be done independently according to the initiative’s specific needs. Conversation with Peggy Fuller, October 17, 2016.

24. Elaine Weiss conversation with Peggy Fuller, October 17, 2016.

25. This is federal funding that is passed down through state agencies/offices.

26. CJ Huff, application for state superintendent of the year, 2013. Data from ACT Profile report, internal Joplin data. The composite ACT score did not change over this time. It stayed steady at 22, but that is essentially a gain, considering that most of the new test-takers are from disadvantaged backgrounds.

27. CJ Huff, application for state superintendent of the year, 2013. Data from ACT Profile report, internal Joplin data.

28. Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, Comprehensive Data System. https://mcds.dese.mo.gov/quickfacts/SitePages/DistrictInfo.aspx?ID=__bk8100030043009300130043008300

29. Scores among disadvantaged subgroups such as black and Hispanic students and students eligible for free and reduced-price lunches also increased substantially, but most of those numbers are too small to detect reliable trends over time. https://dese.mo.gov/top-10-20/data-dashboard.

30. We use the cohort dropout rate rather than the single-year or other dropout rates because it is a more accurate assessment of the performance of a given group of students over time.

31. https://mcds.dese.mo.gov/quickfacts/Pages/Student-Characteristics.aspx.

32. These are from internal data collected by Bright Futures during those years.

33. These are from internal data collected by Bright Futures and school leadership during those years.

34. These are from internal data collected by Bright Futures and school leadership during those years.

35. Bright Futures Joplin Service Learning webpage. http://brightfuturesjoplin.org/service-learning/

36. CJ Huff biography, Executive Speakers Bureau, http://www.executivespeakers.com/speaker/CJ_Huff#sthash.3Zc3QYmP.dpuf.

37. http://jhs.joplinschools.org/about_j_h_s/college__career___technology_focus

38. “Joplin school district earns future ready, Apple awards.” The Apple award “recognizes outstanding schools and programs worldwide for innovation, leadership, and educational excellence.” Its five criteria include: Visionary Leadership, Innovative Learning and Teaching, Ongoing Professional Learning, Compelling Evidence of Success, and a Flexible Learning Environment. http://www.apple.com/education/apple-distinguished-schools/