Context/Need

In the 1990s, the Boston Public Schools district and its schools lacked a systematic approach to connect urban schoolchildren with the rich resources of the city’s community partners and to efficiently address the out-of-school factors impeding students’ academic success, especially for students living in poverty. The city was at a low point in its population, down from over 800,000 in 1950 to under 600,000 throughout the 1990s, while the share of that population that was non-white – Hispanic and Asian in particular – was growing, as was the share that was foreign-born. 1 One in four students was dropping out of city schools before graduation.2

Response

City Connects was created in 1999 as an evidence-based, scalable practice in Boston. Following an initial meeting in the early 1990s focused on addressing out-of-school barriers to learning at a Boston public elementary school, a two-year planning effort developed as a collaboration among Boston College Lynch School of Education, Boston Public Schools, and local partners, including community agencies.

“In an iterative process, [Boston College and Boston Public Schools partners] repeatedly convened school principals, teachers, other school and district staff, representatives of community agencies, and families to develop a system that re-organized the work schools have traditionally done in the area of student support (e.g., the work carried out by school counselors, nurses, psychologists, and community partners). The resulting system met the criteria of best practices and was initially implemented in Boston schools in 2001.”3

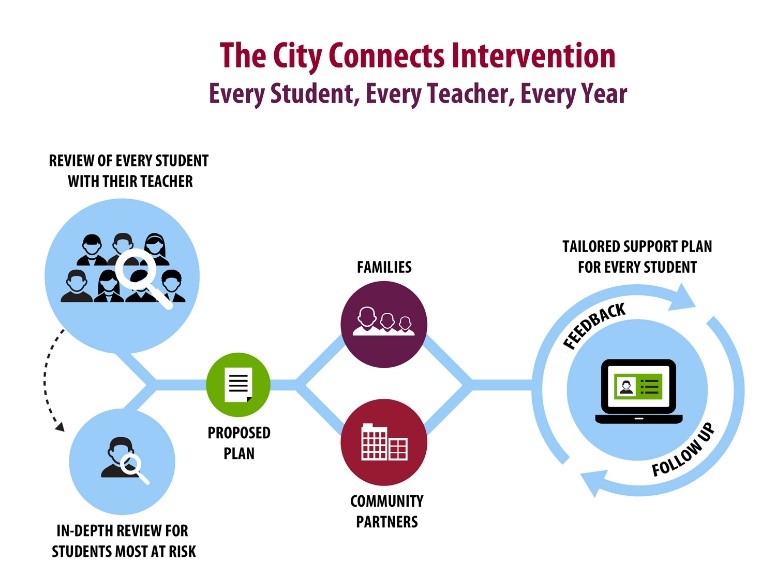

With its foundations in the “full-service” or community school model, City Connects allows districts and schools to wrap needed supports, enrichments, and services around students in order to address barriers standing in the way of school success. The practice engages every classroom teacher, leverages community resources, and ensures that each student receives the tailored supports and enrichment opportunities necessary to learn effectively and thrive in school.

Due to its success, City Connects has been successfully replicated and scaled. It is currently implemented in 100 schools in five states, including other districts in Massachusetts as well as in New York, Connecticut, Ohio, and Minnesota. It will also be in Indiana starting in the fall of 2018.

Strategy for Change

Grounded in evidence, City Connects is a system that organizes student support and leverages existing school and community-based resources in order to improve students’ academic and social-emotional outcomes. As a hub of student support, a full-time social worker or school counselor who becomes the dedicated City Connects site coordinator meets with each classroom teacher and other school staff to identify each child’s strengths and unmet needs. Together, in consultation with families and other adults who know each child, they develop an individualized plan designed to meet the students’ needs and cultivate his or her strengths. Each student is then connected to a tailored set of prevention and intervention services and enrichment opportunities in the school and/or community, with the goal of helping every child to be ready to learn and engage in school.

Using their knowledge of the particular needs of the school, and of gaps in existing services, school site coordinators cultivate partnerships with community agencies, serving as a point of contact for the school. They collaborate closely with families to facilitate access to supports and enrichments. They also use proprietary software to document, track, and report on service referrals for each student, and they follow up to assure service delivery, and assess effectiveness.

Before entering a district, City Connects collaborates with district partners to conduct a needs assessment. The process typically occurs in the spring before the academic year in which the implementation launch is planned. City Connects consults school leaders, teachers, families, and community partners to understand the particular assets and challenges of the community. The process also includes a community scan to identify providers of supports and services in the city. Building on this knowledge, City Connects collaborates with district partners to prepare for launching the intervention.4

Coalition

City Connects draws on a variety of public and private partners to deliver aligned student supports. Its work in Boston Public Schools, its longest-running site, illustrates this collaboration.

Boston Public Schools— In 2017–18, City Connects was operating in 20 Boston public schools with over 8,000 students (pre-K to 8). Approximately half of the students in City Connects schools speak a language other than English at home, and over 80 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

Boston Public Schools— In 2017–18, City Connects was operating in 20 Boston public schools with over 8,000 students (pre-K to 8). Approximately half of the students in City Connects schools speak a language other than English at home, and over 80 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.- Community Agencies—A critical role of the City Connects school site coordinator is developing and maintaining partnerships with community agencies and institutions. In Boston, City Connects has cultivated more than 320 community partnerships that provide resources and support to students and their families. In 2016-17, these partnerships enabled City Connects to connect approximately 8,000 Boston students to 64,940 enrichment opportunities and services delivered by 275 unique providers. Partners include:

- Public: Boston Centers for Youth and Families, Boston Public Health Commission, and the Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation.

- Private: Big Brothers Big Sisters of Mass. Bay, Boys & Girls Club, Salvation Army, and YMCA of Greater Boston.

- Higher Education Institutions: University-based programs include the Boston University Initiative for Literacy Development and the CIVICS Program at Harvard University, a tutoring program at Boston College, and health programs at Tufts Medical Center.

- Boston College—The Center for Optimized Student Support at Boston College co- designed and led the implementation of City Connects in schools, and Boston College’s Center for the Study of Testing, Evaluation, and Education Policy collects, analyzes, and reports on City Connects data. External experts provide independent reviews of the initiative’s methods, results, and conclusions.

- Leadership—City Connects maintains its partnerships with Boston’s community agencies and institutions by convening school-level as well as city-wide meetings of representatives from the school system and community. In addition to sharing aggregate data on services and outcomes, these gatherings focus on issues of current concern, such as support for immigrant families, the needs of homeless students and families, addressing the opioid epidemic, family engagement, and the impact of student health on achievement. The meetings also serve as a way for agencies located across the city to share updates and discover areas of potential synergy.

Comprehensive Services

In order to fulfill its mission of addressing barriers to learning, City Connects works with its coalition partners to provide a range of supports for students and their families. These services are provided through a system that includes assessment of student needs and strengths, development of individualized support plans and of partnerships to support those needs and strengths, tracking, and follow-up.

Assessment—Each school has a licensed school counselor or social worker who serves as a City Connects school site coordinator. There is one coordinator for about every 400 students. The School Site Coordinator works with each teacher to review the strengths and needs of every student in his or her class through a process called the Whole Class Review, which helps identify individual students’ strengths and needs across academic, social/emotional/ behavioral, physical health, and family domains.

Assessment—Each school has a licensed school counselor or social worker who serves as a City Connects school site coordinator. There is one coordinator for about every 400 students. The School Site Coordinator works with each teacher to review the strengths and needs of every student in his or her class through a process called the Whole Class Review, which helps identify individual students’ strengths and needs across academic, social/emotional/ behavioral, physical health, and family domains.- Development of Support Plans—The School Site Coordinator then develops a customized support plan for each student that addresses his or her individual strengths and needs. City Connects is unique in that it focuses heavily not only on meeting student’s needs, but on enhancing their assets. Any given student may receive services in any combination of the following three categories:

- Prevention and enrichment (e.g., sports and physical activity, before- and after- school programs, classes in music, drama, or the arts).

- Early intervention (e.g., tutoring, mentoring, behavior plans, health supports, family outreach).

- Intensive or crisis intervention (e.g., intensive mental health and medical services, violence intervention).

- Development of Partnerships—The school site coordinator identifies and locates appropriate school- and/or community-based services and enrichments and helps establish the connections between these service providers and individual children and their families.

Follow-up—City Connects tracks referrals and service delivery with a proprietary electronic data management system, the Student Support Information System (SSIS), which also houses a database of all City Connects community partners. The system captures information about individual students’ strengths and needs, as identified by the teacher and coordinator in different developmental domains, including academic, social/emotional/ behavioral, health, and family. It provides a way for coordinators to document and track individual service plans. To make the referral process efficient, it includes information about community partners, such as ages served, hours of service, location, and categories of services offered.This system supports appropriate and secure record-keeping at the individual and school level, monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the City Connects practice throughout the school year, and enabling research to be conducted on the effectiveness of the interventions.5

Follow-up—City Connects tracks referrals and service delivery with a proprietary electronic data management system, the Student Support Information System (SSIS), which also houses a database of all City Connects community partners. The system captures information about individual students’ strengths and needs, as identified by the teacher and coordinator in different developmental domains, including academic, social/emotional/ behavioral, health, and family. It provides a way for coordinators to document and track individual service plans. To make the referral process efficient, it includes information about community partners, such as ages served, hours of service, location, and categories of services offered.This system supports appropriate and secure record-keeping at the individual and school level, monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the City Connects practice throughout the school year, and enabling research to be conducted on the effectiveness of the interventions.5

Whole-class review is at the heart of City Connects’ work with the dozens of high-poverty schools it supports. The process provides the kind of personalized learning and support that most schools, even those with much lower levels of severe need, can only dream of. At the start of the school year, the City Connects site coordinator sits down with every teacher to explore each student’s unique strengths and needs. That hour-long meeting enables teachers and coordinators to reflect on the student’s progress over the prior year, identify ways to further advance that progress, and target preventive and remedial supports to unmet needs that may have changed over the year, whether academic, social, emotional, or physical. Students are grouped into tiers that reflect their current mix of strengths and risks across developmental domains. Students in Tier 3 receive the most services, an average of seven, to address their extensive needs and, in many cases, crisis situations. Each school year, 11-12 percent of students are placed in this tier, but due to progress, nearly half move into a lower tier over the course of the school year.

In the Bronx, the process has enabled some of New York City’s highest-poverty schools to ensure that children are connected to the supports many have long lacked, like enriching afterschool opportunities, and empowered teachers to address social, emotional, and behavioral barriers they know their students face to learning effectively. In one Boston elementary school, the information gathered from whole-class reviews led the City Connects site coordinator to develop a Health and Wellness Committee that has brought the school, among other things, Healthy Family Fun Nights, bike helmets, fresh food trucks, a Cooking Challenge, and a garden where students work with faculty and staff to clean up beds, plant the seeds, and watch flowers and food grow. John Winthrop Elementary School site coordinator Jaymie Silverman says she “appreciate[s] the whole class review process because it … also forces us to highlight the strengths of every student. And oftentimes it’s just easy, especially with some of our most challenging students [and in neighborhoods like Dorchester], to get bogged down in the things that aren’t working well and the challenges that teachers encounter on a daily basis.” 6

Early Childhood Education: The City Connects intervention can help all children to learn and thrive in school, but the practice is particularly well-suited to meet the needs and cultivate the strengths of early learners. In the early childhood setting, supports and enrichments can be put in place while critical early development is rapidly evolving. Also, early childhood is a time of strong family involvement, meaning that close family collaboration in development of support plans is often possible. With support from the Better Way Foundation, City Connects has acted on this understanding to implement an Early Childhood adaptation of City Connects, beginning in 2009 in child care settings in Catholic schools, and now in all of its sites that serve an early childhood population. 7

Because parents are so close to their children at this stage and can tell coordinators so much, one City Connects program manager, who was formerly a preschool teacher, has developed a new intake form that asks about issues like family structure, custody issues, bedtime routines, and health screenings and motor skills (e.g., zipping, buttoning, and hopping). Toylee Cigna asks “Can you get family members more engaged in their child’s education process? That may be all that’s needed.” While the focus in early childhood settings is on early childhood development and family engagement, however, the same whole class review and tiered strength-and-risk- mix used in K-12 settings is applied. So a small social skills group might take place in the preschool classroom, and creative use of Legos could be the strength around which a child’s interventions are based. 8

In addition, state and federal early childhood initiatives have boosted City Connects efforts. In prek-5 and prek-8 public schools served by City Connects where UPK classrooms are located, City Connects students benefit from Boston’s high-quality UPK program. Although both federally funded grants have lapsed, some current City Connects students enjoyed early childhood support from state-level NGA and Race to the Top Early Learning Grant initiatives. Boston is also a recipient of the Preschool Expansion Grant, but while that has spurred discussions about moving towards universal prekindergarten in the city, no concrete plan has yet emerged.

Health, Mental, and Dental Health: Because City Connects advances whole-child education, student wellness is at the core of much of its support for students’ health, and supports are targeted based on the type and level of need. Preventive supports, for example, could include the New Balance Health and Wellness Curriculum, while early interventions might involve classroom-based social skills or health interventions. Family counseling, violence intervention, attention to unmet dental needs, and health services to address chronic problems like asthma would be appropriate services for students needing intensive interventions. (City Connects knows that any given student might benefit from less intensive preventive and enrichment services at some points and more intensive/responsive ones in other contexts.)

Coordinators also provide referrals to services in the community and/or school that span these three categories. For example, one coordinator held conversations with parents on nutrition when she met them at the school food bank. This coordinator reported that parents in turn began to focus on nutrition labels when making food selections. In another school, two students who had experienced traumatic injuries were referred for physical activity both to aid in their recovery and to relieve stress. The coordinator worked closely with staff at a YMCA to customize a plan that involved swimming and physical training. 9

In-school and afterschool and summer enrichment: City Connects enables students to leverage the wide variety of enrichment offerings in a city. In Boston, these include youth dance programs offered in collaboration with ballet companies; urban sports programs in biking, rowing, tennis, and lacrosse; and youth development programs offered through community centers and Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs. For Tier I students, the majority of those served by City Connects, programs could be offered before or after school, over the summer, and/or during vacations.

Family engagement: As a regular part of the City Connects practice, Coordinators establish strong ties with families to facilitate communication. When they get to know families or learn from teachers about family strengths and needs, coordinators facilitate referrals to providers of clothing and supplies, parent support, and housing resources.

One Boston teacher says:

Our City Connects coordinator is … not only resourceful and proactive because she establishes and strengthens relationships with community partners, but she simply knows and cares about the students. Talking with her about individuals is always helpful to understanding how students think, get motivated, and ultimately learn.

Foundational Policies and Practices

City Connects’ success in supporting students, its expansion within Boston Public Schools and to other districts and states, and its ability to become self-sustaining is supported by specific practices and policies, both internal to the initiative and based at the local and state levels. Some of these go back to the early days of City Connects, while others are much more recent.

Focus on Resilience and Enhancing Student Strengths

While the needs of many students are extensive, City Connects also believes strongly that students bring unique assets to their classrooms, and that identifying and working to nurture those strengths is key to engaging students and, ultimately, helping them succeed and thrive in school and beyond.

Many students struggle with reading and math proficiency, says Executive Director Mary Walsh, which makes such subjects as music, art, and physical activity all the more important. City Connects enables students to leverage the rich variety of cultural offerings that Boston has to offer, including a wide range of museums, arts classes, and more.

The practice of assessing every student means that teachers and schools can focus not only on needs but on strengths, with the implicit objective of building resilience. City Connects is focused not only on students in serious need, but on a broader range of students who stand to benefit from an emphasis on enrichment over remediation. One example is the small-group health promotion workshops developed and tested by City Connects, which explore such issues as getting along with peers and handling frustration with teachers productively.

The practice of assessing every student means that teachers and schools can focus not only on needs but on strengths, with the implicit objective of building resilience. City Connects is focused not only on students in serious need, but on a broader range of students who stand to benefit from an emphasis on enrichment over remediation. One example is the small-group health promotion workshops developed and tested by City Connects, which explore such issues as getting along with peers and handling frustration with teachers productively.- Because City Connects leverages and builds on a wide range of resources that already exist in the schools and in the surrounding community, it makes civic infrastructure – community agencies, programs, and resources – work better for children and families.

- For example, City Connects works with districts to reinvigorate the work of school counselors, offering successful practices from its model. Therefore, even though this may involve offering new training to existing employees, it can be considered analogous to teachers implementing a new reading or mathematics curriculum, rather than to a change in job description. It also builds on other existing structures, such as Student Support Teams; and aligns with and transforms siloed programs related to student support — like those targeting social-emotional learning, positive behavioral interventions, and multi-tiered systems of support – into a child-centered and effective system of student support.

In the Bronx, City Connects was recruited by the Children’s Aid Society, to deploy its data-based approach to ensure that children in a very high-needs community school did not “fall through the cracks.” In addition to enacting a new theatre program that responded to strengths discovered among a large group of students, City Connects and CAS realized through the whole class review process that they had a large group of new immigrant students, prompting the creation of a newcomers group that enabled students to discuss anxieties about their immigrant status and explore their circumstances in a safe space. 10 This reflects a reallocation of existing personnel resources to be more responsive to student needs.

“I’ve been teaching for 23 years (16 in Boston). This is my toughest class in all years of teaching; academically and socially/emotionally. I’m extremely serious when I say that I’m not sure I would have survived this year without our coordinator.” -Boston Public teacher11

Involvement of District Leadership

School-level efforts tend to be relatively easy to coordinate. The bigger challenge is knitting them together and aligning them with (and getting support for them from) district-level practices. City Connects has benefitted from the start from such support, in particular collaboration with then-Boston Public Schools superintendent Thomas Payzant. The school district did not provide financial support at the outset, but rather offered the use of data to drive practice—reflecting the superintendent’s deep commitment across all aspects of education. The superintendent annually reviewed City Connects’ outcomes, advised the initiative on direction, and supported fundraising efforts. As noted by Mary Walsh, executive director of City Connects and Daniel Kearns Professor at Boston College, “The superintendent’s commitment to an evidence base was aligned with our goals and made it easier to enter Boston Schools.”

- In Springfield (Mass.) Public Schools, where City Connects has been working since 2010, the district builds site coordinator salaries into its budget and has a licensing agreement with City Connects. The agreement includes professional development and training, coaching, program evaluation, fidelity monitoring, technical assistance, and access to the SSIS data system.

The City of Salem, under the leadership of Mayor Kim Driscoll, linked City Connects’ work to a broader citywide effort called Our Salem, Our Kids.

State Education Reform Act

Massachusetts state education reform policies, which were initiated in 1993, have long included a focus on supporting students with extensive out-of-school challenges. City Connects closely aligns with the state’s growing emphasis on creating safe and supportive school environments and meeting students’ comprehensive needs so that they are ready to learn and engage in school.

City Connects was designated by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education as a “Priority Partner” in the state’s efforts, since 2011, to promote wraparound services in school districts.12 This designation allowed districts seeking a wraparound strategy as a lever for school turnaround to choose City Connects as the provider. The State also supported City Connects to study sustainability for interventions that address out-of-school challenges for children living in poverty.

Health Care

Health care policy changes have made it possible for City Connects staff to refer students to essential routine and episodic health care services. In 2006, Governor Mitt Romney passed health reform to provide near-universal health insurance coverage for Massachusetts that included an individual mandate. The proportion of the state’s population that had health insurance rose from 90 percent to 98 percent, the highest in the country, and as of 2011, virtually all children—99.8 percent—had health insurance coverage.13

The law also expanded Medicaid enrollment for adults and children with disabilities and the long-term unemployed and raised the family income ceiling for the Children’s Health Insurance Program from 200 percent of the federal poverty level to 300 percent.14 While City Connects has no direct access to Medicaid funds, it has established a consistent practice of talking to families and providers about drawing on Medicaid coverage to support both physical and mental health services. The initiative also ensures that it refers students who require such care to insurance-eligible providers.15

Most recently, the state announced a Medicaid waiver that will allow schools to seek reimbursement for health, mental health, and dental services for all students in need, not just those with an Individual Education Plan/IEP. The waiver policy will go into effect in July 2019.

Pre-K

Various state funding streams support enrollment in pre-k classrooms for children with special needs and their typically developing peers in public school classrooms. City Connects has begun to align its implementation with this emphasis on early childhood by expanding the intervention to this age group, and most of the children it serves are in such classrooms. 16

Massachusetts was also awarded a federal Preschool Expansion Grant that was used to support the expansion of pre-K across the mixed delivery system (ie public schools, private non-profit community-based providers, Head Start) in five Massachusetts cities (Boston, Springfield, Holyoke, Lawrence, and Lowell). There is a provision in that grant to include “comprehensive services,” and that has been variously interpreted in the five communities. In Springfield, the city created an early learning center that brings all of these different providers under one roof. City Connects is serving in the early learning center. The PEG grant is in its final year, however, and the state does not have a plan for continued funding. 17

School Turnaround

Although state and federal policies have generally been limited in their inclusion of student support initiatives, City Connects has been able to engage in school “turnaround” efforts through federal School Improvement Grants (SIGs) as well as leveraging state-level policies.

- As part of the state’s federal Race to the Top grant, which has now expired, City Connects was selected by district administrators as one of the levers for school turnaround in Level 4/5 schools. SIG funds also helped support some of these efforts. The state also had its own “Wraparound Zone” initiative parallel to efforts under federally funded SIG, though these no longer are in operation. Springfield, which was among the districts with schools targeted for wraparound turnaround models, chose City Connects to be its partner. Other districts chose to use self-described “homegrown models.”

- Student support was a priority of the previous state Secretary of Education, Paul Reville, but his proposal to fund it in Mass.’s 24 “Gateway Cities” was not approved in the governor’s 2013 budget.

Recent foundations for ISS:18

The state’s 2008 passage of the Act Relative to Children’s Mental Health, which established a Behavioral Health and Public Schools task force, set in motion collaboration between schools and behavioral health service providers. The task force’s final report, in 2011, provides a three-part self-assessment tool for schools to prevent and address student mental health problems. This law, along with a 2010 bullying prevention law, laid the foundations for the 2014 Act Relative to the Reduction of Gun Violence, which established a Safe and Supportive Schools Commission to advance implementation of the Safe and Supportive Schools Framework. In 2015, this became a core state education priority, and the Commission is developing a statewide framework to help schools integrate social-emotional learning and behavioral health, including community-based resources to provide them, into their work. In all, these laws promote the early identification and prevention of behavior and mental health problems and help equip schools to address them.

At the same time, former Governor Deval Patrick initiated efforts to advance inter-agency collaboration, including the establishment of the Child and Youth Readiness Cabinet, which brings together the Departments of Education, Health and Human Services, and several others that touch children.19 The cabinet worked toward an early warning system to identify children at risk of failure and explored the creation of a statewide data reporting system to ensure smooth sharing and transfer of key information. While Governor Baker disbanded the cabinet, much of the collaborative work has been sustained, and an executive order funds 18 Family Resource Centers across the state that provide a range of parenting and family and child support resources.

The state education department has also made progress on an early warning indicator system that uses data to identify students in all grades at risk of failure so that schools can target appropriate supports, both academic and non-academic, to get them back on track. Some districts use Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, and data sharing across agencies allows schools to enroll eligible students for supports like subsidized school meals or Medicaid. And in 2018, Governor Charlie Baker established a new interagency working group focused on preventive and systemic approaches to student support that includes staff from two key departments: Elementary and Secondary Education and Health and Human Services.

Funding

The Center for Benefit-Cost Studies in Education at Columbia University conducted an independent analysis that estimated the cost to implement City Connects at about $250 per pupil per year (excluding the costs of community services). A more recent study finds that schools currently spend roughly $150 per year on student supports, and that City Connects adds about $130 to that. This cost is shared by public and private funders.

Public

Some federal and state funding, including Race to the Top funding allocated by districts to City Connects, has helped to defray these costs. In addition, districts have contributed by including City Connects in their budgets.

Private

City Connects has been supported by a number of foundations, including the Charles Hayden, Barr, New Balance, Mathile Family, and Better Way Foundations, Strategic Grant Partners, and the Philanthropic Initiative. These partners have supported central program implementation and/or evaluation.

Indicators of Progress

These comprehensive changes to how schools are structured and the way they link students to needed supports have resulted in a range of benefits, both academic and other. 20 Longitudinal, peer-reviewed evidence shows that students in City Connects schools have better effort, grades, and attendance and that the model can significantly narrow achievement gaps and reduce high school drop-out rates. And principals and teachers report significant benefits to school climate, job satisfaction, understanding of the whole child, and improved teacher-student relationships.

Academic/student gains

Student performance and principal satisfaction measures document academic and student gains. Over a decade of rigorous, peer-reviewed research on City Connects finds that students enrolled in a City Connects elementary school have significantly higher performance in both academic and so-called noncognitive skills not only in those years, but also after they leave City Connects and enroll in secondary school.21The benefits are often greatest for the most at-risk students, particularly English Language Learners.

- City Connects elementary school students achieve higher scores than their non–City Connects peers in reading and math on the Stanford Achievement Test version 9 (SAT-9).22 Effect sizes were large, between one quarter and half of a standard deviation. City Connects students also do better on other, noncognitive outcomes contributing to academic success: behavior, effort, and work habits.

- Students who had received City Connects support during elementary school were followed into middle school. On the Massachusetts statewide test, City Connects students closed two-thirds of achievement gaps on math and half of the achievement gap on English compared to their peers who did not receive City Connects.

- Although they have similar rates of chronic absenteeism in elementary school, where absenteeism is not a major problem, by middle and high school (where it is), City Connects students have significantly lower rates than their comparison peers.23

- Students previously enrolled in City Connects are more likely to attend one of three of Boston’s selective public high schools (“exam schools”), with the odds of exam school attendance increasing for each year a student participated in City Connects.

- Students who participated in City Connects in kindergarten through fifth grade are less likely to be held back in a grade and are only about half as likely as comparison students to drop out of high school.

- More recent research has looked at the impacts of City Connects on vulnerable subgroups. It has been found to be especially beneficial to immigrant students and English Language Learners (Dearing, 2016). Reductions in high school drop-out rates were as strong, if not better, for black and Latino boys (see drop-out brief 2017).

- While the rate of referrals of students to special education services has not decreased, City Connects staff reports that, due to site coordinators’ improved understanding of individual students’ needs, the referrals are more accurate. This means that those students who are referred to special education evaluations are more likely to have a disability and actually need special education services, while schools are not paying for services for students who do not need them and would not benefit from them.

“City Connects provides the support and services that otherwise would be missing at our school. Without this program many of our students would be lost.” -Boston Catholic school principal

Successful, rigorous implementation has expanded work in Boston

- Based on promising data, district leaders enabled City Connects to launch a replication in eight additional schools in 2007. They provided critical support as funders weighed the evidence in funding decisions.

- When the district saw evidence of positive longitudinal outcomes in 2010, it not only asked for a further expansion to the newly identified Turnaround schools, but also agreed to contribute a portion of the costs. In 2014–15, City Connects was included as a line item for the first time in the Boston Public Schools budget.

- Currently, City Connects has a waiting list of schools seeking implementation if funds become available.

- Principals and teachers are highly satisfied with City Connects. A study of teachers’ experiences shows that City Connects improves their understanding of the whole child, helps them to feel more supported in their jobs, and improves their job satisfaction and understanding of students.24 In an anonymous electronic survey, teachers report high levels of satisfaction with City Connects. For example, 97 percent of teachers surveyed in Boston Public Schools would recommend City Connects to a colleague.25In both Boston and Springfield, 100 percent of principals reported that they were satisfied with City Connects and that improves their schools’ climate and said that they would recommend City Connects to a principal in another school. Perhaps most important, 86 percent of Boston and 100 percent of Springfield principals indicated that City Connects has improved their schools’ delivery of student support.26

City Connects Has Expanded Across and Beyond Massachusetts

- Success in Boston led Springfield to seek City Connects as a turnaround strategy. During its first four years in Springfield, Mass., the district asked City Connects to expand from six to 13 schools. It has since further expanded, adding eight new schools in 2017-18 to bring the total to 23. Evidence of successful scaling is evident in measurements of fidelity of implementation of the model across program sites. For example, the 2014 Progress Report notes that:

Across the Springfield schools implementing City Connects, 91% of Springfield City Connects students received at least one service. Additionally, more than 80% of the students received three or more district- or community-provided services. These percentages …are similar to Boston, where 98% of students received at least one service and 81% received three or more services.17

- In Salem, Massachusetts, City Connects coordinators are in all eight of the district’s K-8 schools. In consultation with the local union, district leadership decided to repurpose existing school counselors and social workers to become trained as City Connects coordinators, since the City Connects counselor role is closely aligned with the professional standards for school counselors and social workers.

- Over time, City Connects has expanded beyond Boston and presently serves over 30,000 students in 12 cities across five states: Massachusetts, Connecticut, Minnesota, New York, and Ohio, with plans to expand as well to Indiana starting in fall 2018. (In 2016-17 City Connects connected 27,005 students to 212,319 services delivered by 1,249 unique providers.) Approximately one in five of those students speaks a language other than English at home, and over 90 percent are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. A sophisticated technology system allows for monitoring of fidelity of implementation, data driven continuous improvement, and outcome evaluation. Learning management systems are in use to support ongoing professional development, in addition to coaching and resources provided to support the City Connects practice at scale.

City Connects’ Success Has Begun to Influence Policy

Under cost assumptions most consistent with data on implementation, a report produced by Columbia University’s Center for Benefit-Cost Studies estimates the return on investment at 3:1, meaning society will save three dollars for every dollar it invests in the City Connects model. (That 3:1 includes the costs of all services – health care, social services, after school programs, etc. – for children and families.) If the costs to community partners are excluded, as they are in most benefit-cost analyses of comparable programs, the benefit-cost ratio is 11:1.27 The success of City Connects has led to its use as an example of a comprehensive approach to education that can be scaled and adapted elsewhere, greatly enhancing its potential policy impact.

- In its 2015 Annual Report on the State of Education in the Commonwealth, the Rennie Center for Education Research and Policy pointed to City Connects as a scalable, evidence-based approach for a robust statewide approach to student support.28 The report promoted investment in broader implementation of holistic assessments of student well-being, in addition to effective multi-provider models that allow schools and their partners to address a full range of student strengths.

- City Connects was recognized by Child Trends as one of three evidence-based approaches to addressing the out-of-school needs of students.29 This Washington- based independent organization conducts research on issues impacting children and informs policymakers through meetings, briefs, and reports.

Evidence of City Connects’ impact and positive ROI have prompted momentum toward integrated student support broadly: a state senate vision document that includes integrating comprehensive supports; language and funding supporting ISS in the FY18 budget; a state commission that has incorporated and formally filed principles of effective practice for integrating student supports; legislation proposed by the Governor; and a new interagency working group. In addition, in his annual address to the House Chamber, the Speaker of the House recently made meeting students’ comprehensive needs a priority:

And once children reach school age, we similarly recognize the need to provide effective student supports that go beyond academia. But we also realize that our schools cannot do it alone. Therefore, we will build on our Safe and Supportive Schools initiative – created in the 2014 Gun Law – to help schools integrate student supports, leverage preexisting investments, and coordinate school and community-based resources.30

Contact

Mary Walsh, Executive Director, [email protected], or visit www.cityconnects.org

Endnotes

1. Mark Melnik, “Demographic and Socio-Economic Trends in Boston: What we’ve learned from the latest Census data,” Boston Redevelopment Authority. Nov. 29, 2011. http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/70ddddcd-760f-49fa-a32e-fb5a80becd34.

2. As per cohort dropout rates for the 9th-1th grade cohort from 1995-2000, https://www.bostonpublicschools.org/cms/lib/MA01906464/Centricity/Domain/238/Dropouts%20SY15%20complete.pdf.

3. City Connects, Story of our Growth. http://www.bc.edu/bc-web/schools/lsoe/sites/cityconnects/our-approach/story-of-our-growth.html

4. Citation can be the forthcoming 2018 Progress Report.

5. Data from SSIS are used in City Connects’ fidelity monitoring system. The system provides quantitative evidence of the degree to which the model has been implemented as designed. Data from the system also provide key evidence for outcome evaluation.

6. https://cityconnectsblog.org/2016/12/01/the-power-of-whole-class-reviews/#comments

7. M. E. Walsh, John T. Lee-St. John, A. Raczek, C. Foley, and E. Sibley, “The City Connects Early Childhood Model: Implementation and Results.” Poster submitted to the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Philadelphia, PA, April 2015.

8. https://cityconnectsblog.org/2017/04/27/city-connects-in-early-education-settings/

9. Citation is the City Connects 2018 Progress Report, to appear in the next month.

10. City Connects Kappan article.

11. From anonymous teacher survey conducted by City Connects. Year?

12. Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, “Priority Partners for Turnaround” on Mass.gov

13. Kaiser Family Foundation, “Massachusetts Health Care Reform: Six Years Later.” May 2012.

14. It has since been up to the governor to implement the law. Almost 100 percent of children are covered by health insurance, and the focus now is to control the cost of healthcare, which has been increasing; originally 36 percent of the state budget in 2006, it was 43 percent in 2011.

15. Information from Elaine Weiss conversation with Mary Walsh, January 12, 2016.

16. M. E. Walsh, John T. Lee-St. John, A. Raczek, C. Foley, and E. Sibley, “The City Connects Early Childhood Model: Implementation and Results.” Poster submitted to the annual meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development, Philadelphia, PA, April 2015.

17. Separately, City Connects is in a couple of stand-alone early education and care centers and some of the children in those centers receive vouchers (state-federal CCDBG funding).

18. Tipping the Scales report. URL.

19. These include Administration and Finance, Housing and Economic Development, Labor and Workforce Development, Public Safety, and the Child Advocate.

20. All data points noted here are from the 2014 Progress Report unless otherwise indicated. The 2010 report compared Boston City Connects schools with 7 randomly selected comparison schools. The 2014 report compares all City Connects Boston to all non-City Connects Boston schools.

21. M.E. Walsh, G.F. Madaus, A.E. Raczek, E. Dearing, E., C. Foley, C. An, T.J. Lee-St. John, and A. Beaton, “A New Model for Student Support in High-poverty Urban Elementary Schools: Effects on Elementary and Middle School Academic Outcomes.” American Educational Research Journal, 51 (4), 704–737, July 7, 2014.

22. Based on 2001–2009 data, as reported in the 2012 progress report.

23. Because it is not a state standardized test, the SAT-9 is not subject to the “teaching to the test” nor other problems associated with trying to artificially inflate results. As City Connects notes, SAT-9 scores have been found to be strong predicators of high school graduation. As such, these data provide a useful comparison of meaningful improvement in academic outcomes that is likely the result of City Connects participation.

24. Sibley, E., Theodorakakis, M.A., Walsh, M.E., Foley, C., Petrie, J. & Raczek, A. (2017). The impact of comprehensive student support on teachers: Knowledge of the whole child, classroom practice, and teacher support. Teaching and Teacher Education 65, 145-156.

25. City Connects (2014), p. 41–44

26. City Connects (2014), p.40.

27. A. B. Bowden, C.R. Belfield, H.M. Levin, R. Shand, A. Wang, and M. Morales, A Benefit-Cost Study of City Connects, Center for Benefit-Cost Studies of Education, Columbia University, July 2015.

28. Rennie Center for Education Research & Policy, Achieving the Vision: Priority Actions for a Statewide Education Agenda, Boston, MA, Winter 2015.

29. K.A. Moore, S. Caal, R. Carney, L. Lippman, W. Li, K. Muenks, D. Murphey, D. Princiotta, A.N. Ramirez, A. Rojas, R. Ryberg, H. Schmitz, B. Stratford, and M.A. Terzian, Making the Grade: Assessing the Evidence for Integrated Student Supports, Child Trends. February 2014.

30. Speaker DeLeo’s 2017 Anniversary Address to the House Chamber setting forth his priorities for the coming session (January 30, 2018